The first pilot activity in the context of the Mare Nostrum (MN) Project took place from 27 May to 27 June 2010 through field work by Carla Zickfeld, MN project coordinator, Stefan Karkow, documentalist, Aliou Sall, Senegalese coordinator, and several collaborators, including Oumar Sow and Ousmane Niang (Click on the name to see the short video). Photos and videos by S. Karkow.

The objective of this phase of MN in 2011 is to build up a solid documentary base together with social actors in the fisheries sector and related activities so as to enhance mutual understanding and trust. The fishermen, women fish processors and marketers and many others involved in the fishing industry and its social make-up in coastal towns are all caught between traditional practices and beliefs and rapid modernisation driven by integration into a truly global economy.

The objective of this phase of MN in 2011 is to build up a solid documentary base together with social actors in the fisheries sector and related activities so as to enhance mutual understanding and trust. The fishermen, women fish processors and marketers and many others involved in the fishing industry and its social make-up in coastal towns are all caught between traditional practices and beliefs and rapid modernisation driven by integration into a truly global economy.

This creates many frictions and is further aggravated by rampant overfishing that affects the very basis of their livelihoods. The erosion of their social and economic livelihoods can be halted and reversed. There is a wealth of experience within the fishing communities and ample possibilities to connect ideas from within and without to work on transformations which can create improvements. Despite the fact that a few people may still be living in a state of denial, rebuilding productive marine ecosystems would be an obvious benefit to all concerned. So, the big issue is not so much whether protecting the resource-base would be good, but rather how to do it. That boils down to a question of how the costs and the benefits will be distributed, a pattern seen across many resource sectors and countries. There seems to be little trust even among different interest groups within the fisheries sector and even less so at the moment vis-à-vis the government, especially since additional licences were granted in May 2011 to foreign vessels, while the domestic operators face major problems and fear they will further loose out in this additional competition over already scarce resources. The increasingly lofty discussions in a series of workshops with international public organisations and NGOs that have taken place over the last few weeks do little to instil a sense that concrete action would be taken to address the open crisis.

So it falls back to the operators in the small-scale fishing sector, the women and the representatives of their professional organisations to demand pragmatic remedial steps and greater fairness and transparency in the way the sector is run. They did that with protest marches in Dakar and with fresh appearances in the European Parliament in Brussels and elsewhere in May and June 2011. They are striving to block inconsiderate privileges of investors, foreign and domestic, who operate with little regard for the long-term viability of operations as their principal concern is a short-term return on their investment. So, today it's the marine ecosystem from which to extract through fishing and marketing, tomorrow it may be something else. When the resource is gone they move on, leaving behind a trail of destruction, as we have already seen in the collapse of one fishery after the other in the North Atlantic and elsewhere. Then the people are left with ghost towns where there were once bustling communities, as is the case in Lowestoft, UK, and elsewhere. It's not too late to act to prevent a similar fate for the fishing communities in Senegal and other West African countries.

So it falls back to the operators in the small-scale fishing sector, the women and the representatives of their professional organisations to demand pragmatic remedial steps and greater fairness and transparency in the way the sector is run. They did that with protest marches in Dakar and with fresh appearances in the European Parliament in Brussels and elsewhere in May and June 2011. They are striving to block inconsiderate privileges of investors, foreign and domestic, who operate with little regard for the long-term viability of operations as their principal concern is a short-term return on their investment. So, today it's the marine ecosystem from which to extract through fishing and marketing, tomorrow it may be something else. When the resource is gone they move on, leaving behind a trail of destruction, as we have already seen in the collapse of one fishery after the other in the North Atlantic and elsewhere. Then the people are left with ghost towns where there were once bustling communities, as is the case in Lowestoft, UK, and elsewhere. It's not too late to act to prevent a similar fate for the fishing communities in Senegal and other West African countries.

It is against this backdrop that the Mare Nostrum pilot work was carried out throughout June 2011. Starting with the documentation of the memories and vindications of the women in the fishing sector, the MN team will produce multi-media and educational documentation, including books, a documentary and later also an art film so as to strengthen the knowledge basis which informs the social and political debate and, hopefully, the choices for policies and action.

It is against this backdrop that the Mare Nostrum pilot work was carried out throughout June 2011. Starting with the documentation of the memories and vindications of the women in the fishing sector, the MN team will produce multi-media and educational documentation, including books, a documentary and later also an art film so as to strengthen the knowledge basis which informs the social and political debate and, hopefully, the choices for policies and action.

In the following pages therefore, summaries of conversations with key groups of fishermen, women in the fishing sector, schools and others will be documented as factually as possible and more material will be added as it becomes available. The intention is to give a greater voice to the directly concerned local actors, whether we agree with all they have to say or not. They are the experts on impact as they experience the negative effects of many previous projects, whose intentions have sometimes been perverted in the course of implementation.

It's time to learn these lessons and and develop practical alternatives that are more robust than previous attempts because they are build on a wider spectrum of perspectives. As a result, one may hope that they also command more support from the different groups involved and/or affected. Most importantly, they may therefore stand a greater chance of being implemented compared to many previous attempts led by technical expert opinion which could not always capture the many unintended consequences in social or economic effects and have thus not always had the planned beneficial effects.

The lessons learnt and perspectives shared below will be carried forward in contexts other than the Mare Nostrum Project, which is now closed.

Report of the visit to wholesalers and fishmongers in Hann

We went to the beach in Hann (Yarakh in Woloff) on Wednesday, 01/06/2011, to meet the various actors in the fisheries in Senegal. The first step was meeting with wholesalers who received us at the offices at the landing place in Hann. The session began with self-presentations by the participants, including people living in Hann and the delegation of Mundus maris / Mare Nostrum led by Carla, who was assisted and Stefan and, for the occasion, by Oumar Sow, a member of the local MM team. Following this presentation, Carla, in her capacity as coordinator of Mare Nostrum, opened the discussion by asking questions relating to key challenges the people active in the fishery face and the solutions they recommend. Babacar Mbaye, called "Mbaye Rokh," representing the range of wholesalers Hann, explained the main constraints to the development of their activities, supported in this by his fellow wholesalers. They first defined the activity of fish traders as that of purchasing seafood directly from fishermen to sell the fish either to companies that process or export it to overseas or to women fish vendors there or in the villages.

We went to the beach in Hann (Yarakh in Woloff) on Wednesday, 01/06/2011, to meet the various actors in the fisheries in Senegal. The first step was meeting with wholesalers who received us at the offices at the landing place in Hann. The session began with self-presentations by the participants, including people living in Hann and the delegation of Mundus maris / Mare Nostrum led by Carla, who was assisted and Stefan and, for the occasion, by Oumar Sow, a member of the local MM team. Following this presentation, Carla, in her capacity as coordinator of Mare Nostrum, opened the discussion by asking questions relating to key challenges the people active in the fishery face and the solutions they recommend. Babacar Mbaye, called "Mbaye Rokh," representing the range of wholesalers Hann, explained the main constraints to the development of their activities, supported in this by his fellow wholesalers. They first defined the activity of fish traders as that of purchasing seafood directly from fishermen to sell the fish either to companies that process or export it to overseas or to women fish vendors there or in the villages.

The oldest among the fishmongers present at the meeting attested to the good health of their business in the past despite the modest and very basic traditional working means available to them. They said they did not need ice to preserve fish because it was selling fast and they it put on carts to sell in the neighborhoods. The current situation is alarming, they say, and a united reaction by the real actors of the fishery is needed. Among the difficulties that Mr. Mbaye Rokh mentioned, we note:

The oldest among the fishmongers present at the meeting attested to the good health of their business in the past despite the modest and very basic traditional working means available to them. They said they did not need ice to preserve fish because it was selling fast and they it put on carts to sell in the neighborhoods. The current situation is alarming, they say, and a united reaction by the real actors of the fishery is needed. Among the difficulties that Mr. Mbaye Rokh mentioned, we note:

-

An inability to meet the administrative requirements imposed by banks: the guarantees to be produced for the acquisition of funds from lending institutions are very heavy and therefore the fish vendors often lack the means to start or to continue their activities;

-

Enormous difficulties to equip themselves with appropriate trucks that could be related to the current policy of the Senegalese authorities, resulting in:

Enormous difficulties to equip themselves with appropriate trucks that could be related to the current policy of the Senegalese authorities, resulting in:-

Lack of administrative measures to cushion the exorbitant cost of these refrigerated trucks and their poor quality;

-

The legislative ban on cars allowed to enter Senegal, a restriction which is at the same time an obstacle to the acquisition of certain quality vehicles.

-

-

A lack of vision and lack of willingness on the part of public authorities to provide a solution to the old problem of the preservation of products: the fishmongers and especially the women fish mongers denounced in fact a great need in cold rooms to ensure conservation of their products. Without a solution to the problem of conservation, fish traders continue to depend on the supply of ice at a high price that can climb up to 3000 FCFA or even 4000 FCFA per kilo;

-

Unfair competition they face from foreign wholesalers (Burkina Faso, Mali), who benefit from support by their governments and from the area of free movement of goods and people instituted by ECOWAS.

And they denounce the silence, the laxism and inertia of state authorities to deal with their difficulties and propose all the same some solutions so that the actors in the fisheries can enjoy the fruit of their work and that fishing becomes more transparent and is sustainable.

We then made for the women fish vendors and were received by the ladies Fatou Diop NIANG and Khady FALL, called "Sela", both officials and representatives in Hann, Senegal (National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen in Senegal: CNPS). They gave us an idea of how their activities of selling and trading fish, too, are not always rewarded for their efforts, because they have difficulties with the acquisition and distribution of fish. They started with acknowledging the fishermen who, they say, are the bravest players in the fishery and in spite of that suffer more than any other.

We then made for the women fish vendors and were received by the ladies Fatou Diop NIANG and Khady FALL, called "Sela", both officials and representatives in Hann, Senegal (National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen in Senegal: CNPS). They gave us an idea of how their activities of selling and trading fish, too, are not always rewarded for their efforts, because they have difficulties with the acquisition and distribution of fish. They started with acknowledging the fishermen who, they say, are the bravest players in the fishery and in spite of that suffer more than any other.

Women fish traders have denounced the scarcity of resources. Depending exclusively on the sale of fish as a source of income, fishmongers consider the scarcity of resources is the biggest worry hanging over them. Another concern relates to the fact of the character of Hann as a traditional fishing village. This tends to disappear because most young people are no more attracted to this activity which is not rewarding to the practitioners, they suffer more than they earn. The acquisition of funds to support them and spare them the risk of cessation of activity is also a problem of these women, who often are not educated enough to take the appropriate counter measures.

Women fish traders have denounced the scarcity of resources. Depending exclusively on the sale of fish as a source of income, fishmongers consider the scarcity of resources is the biggest worry hanging over them. Another concern relates to the fact of the character of Hann as a traditional fishing village. This tends to disappear because most young people are no more attracted to this activity which is not rewarding to the practitioners, they suffer more than they earn. The acquisition of funds to support them and spare them the risk of cessation of activity is also a problem of these women, who often are not educated enough to take the appropriate counter measures.

They claim to have charges greater than those of wholesalers because they also have to buy ice to keep their fish and they must pay more for young men so that their products reach the sales sites.

They claim to have charges greater than those of wholesalers because they also have to buy ice to keep their fish and they must pay more for young men so that their products reach the sales sites.

They also denounce the fact that only the fishermen talk of the problems of fishing, while others are in their offices owning sea-going canoes remain unresponsive, while it is they who earn more than fishers and do not suffer.

After recalling that they were the main breadwinners of their families, the women have developed solutions and ideas to restore the former luster of fishing and preserve the cultural identity of Hann.

Faced with these difficulties, before adjourning the meeting and to provide alternatives, the women fishmongers issued a vow to the Mundus maris mission to work together in the coming years to explore the perspectives provided by:

Faced with these difficulties, before adjourning the meeting and to provide alternatives, the women fishmongers issued a vow to the Mundus maris mission to work together in the coming years to explore the perspectives provided by:

-

The establishment of marketing cooperatives or other type of organisation adapted locally to improve working conditions and lives of these women culturally but also economically dependent on fishing;

-

Prospecting work in Europe sought by the wholesalers and especially women fishmongers for which they hope to get the help of the delegation of Mundus maris to help them identify alternative solutions to the conservation of fishery products, given that Mundus maris is not involved in large investment projects;

-

The idea of implementing a pilot project towards the creation of a social security fund for fishermen so that they can still be supported when they are no longer able to carry out their activities (illness or retirement); in the first place, the initiative should target women.

The idea of implementing a pilot project towards the creation of a social security fund for fishermen so that they can still be supported when they are no longer able to carry out their activities (illness or retirement); in the first place, the initiative should target women.

Click here to see a slide on the Mundus maris channel show about the ground realities in Yoff and Hann.

Click here to see a slide show video on the Mundus maris channel about the activities of Fatou and Sela as fish mongers in Hann.

All photos by Stefan Karkow.

Modernisation tends to squeeze out women fish traders

Fatou and Sela as fishmongers: a sense and an importance to be understood in an area under the influence of modernisation:"If our living conditions do not change, in perhaps 10 or 15 years our traditional artisanal fishing village will no longer exist!"

Fatou and Sela as fishmongers: a sense and an importance to be understood in an area under the influence of modernisation:"If our living conditions do not change, in perhaps 10 or 15 years our traditional artisanal fishing village will no longer exist!"

The significance of continued engagement in the fish trade of Fatou and Sela needs to be explained for those who are not aware of the profound changes the artisanal fishery has undergone in recent years. Traditionally, fishing is organised in a family and for this reason, the canoes have always been family-style.

But as a result of the high rents in the fishery, more and more people from outside the fishing communities have invested in the sector. That's why we have several people who have amassed profits in various sectors and have invested in the fishery by becoming owners of fishing units. Those people who invest can be individuals or export-oriented factories as is the case in Hann.

The increasing importance taken by these new investors from outside the fishing communities has profoundly affected the internal workings of these communities. Indeed, the modernisation of the artisanal fisheries sector was carried out with significant social costs.

The goal here is not to propose a thorough analysis of the impacts, but we may mention one of the most visible consequences: that "the modernisation taking place with more investments does not allow women to have the same roles as before and that they gradually lose the benefit of wholesalers men. Many women fish traders have become micro-fishmongers."

It is in this context that we appreciate the role and the unique place occupied by people as Fatou and Sela, who are among the few women who continue to maintain their role as "family fishmongers". These two women are from among the two oldest fishing families in Hann. Family fishing units in their care are purse seines, whose acquisition requires a significant capital.

It is in this context that we appreciate the role and the unique place occupied by people as Fatou and Sela, who are among the few women who continue to maintain their role as "family fishmongers". These two women are from among the two oldest fishing families in Hann. Family fishing units in their care are purse seines, whose acquisition requires a significant capital.

Faced with the difficulties of access to formal credit in order to maintain family ownership, these two families develop various strategies in the circuit and family support networks they are associated with: participation in several tontines, diversification of activities through engaging in small commerce, etc.

The day of a micro fish-vendor in Senegal

On Friday, June 10, 2011 we went to Ms Astou Gueye, a micro fish-vendor in Yoff, who had willingly agreed that we accompanied her throughout her workday to make us more aware of the difficulties she faces, and which she and her fellow micro-fishmongers had explained to us.

On Friday, June 10, 2011 we went to Ms Astou Gueye, a micro fish-vendor in Yoff, who had willingly agreed that we accompanied her throughout her workday to make us more aware of the difficulties she faces, and which she and her fellow micro-fishmongers had explained to us.

The day begins at 8 am when she leaves her house to go to the beach to buy fish to complete the stock she has kept at her home. It happens that the day ends and she has not sold all the fish available to her. For the conservation of the fish remaining at the end of the day, she has a carcass of an old freezer without engine, into which she puts ice at her disposal in order to put the fish on the market the next day 1). The unfinished building in the background of the photo to the right was supposed to be an ice-making plant.

The day begins at 8 am when she leaves her house to go to the beach to buy fish to complete the stock she has kept at her home. It happens that the day ends and she has not sold all the fish available to her. For the conservation of the fish remaining at the end of the day, she has a carcass of an old freezer without engine, into which she puts ice at her disposal in order to put the fish on the market the next day 1). The unfinished building in the background of the photo to the right was supposed to be an ice-making plant.

When the income earned the previous day is quite interesting, she can buy directly from wholesalers at the beach and sell the fish directly to her fellow micro-fishmongers.

When the income earned the previous day is quite interesting, she can buy directly from wholesalers at the beach and sell the fish directly to her fellow micro-fishmongers.

Otherwise, she buys out of the market from them. No doubt that in this second case the benefits will not be as interesting. She then returns home to prepare for the day.

Otherwise, she buys out of the market from them. No doubt that in this second case the benefits will not be as interesting. She then returns home to prepare for the day.

Arrived home, she goes through the selection of fish she will take to the market. Fish available to her are varied: Barracuda (Sphyraena sphyraena), African Red Snapper (Lutjanus agennes), Bigeye scad (Selar crumenophthalmus) and so on. Once done, she gives her grown children instructions for the care of the smallest and the management of the house until her return.

Arrived home, she goes through the selection of fish she will take to the market. Fish available to her are varied: Barracuda (Sphyraena sphyraena), African Red Snapper (Lutjanus agennes), Bigeye scad (Selar crumenophthalmus) and so on. Once done, she gives her grown children instructions for the care of the smallest and the management of the house until her return.

She finally makes for the market and goes off to the garage where she will wait for three other vendors with whom she shares the price of the taxi.

She finally makes for the market and goes off to the garage where she will wait for three other vendors with whom she shares the price of the taxi.

Astou Gueye goes to the market of Grand-Yoff and the taxi will stop at a place from where she will walk to her preferred customers to deliver the orders received the previous day.

Astou Gueye goes to the market of Grand-Yoff and the taxi will stop at a place from where she will walk to her preferred customers to deliver the orders received the previous day.

She still walks long distances with the plastic bowl on her head that contains the merchandise and can weigh between fifteen (15) and twenty (20) kg. She walks shouting out the varieties of fish on offer so as to make potential buyers well aware of her passage.

She still walks long distances with the plastic bowl on her head that contains the merchandise and can weigh between fifteen (15) and twenty (20) kg. She walks shouting out the varieties of fish on offer so as to make potential buyers well aware of her passage.

Once she has completed the round, she goes to the fixed location where she sells fish.

Once she has completed the round, she goes to the fixed location where she sells fish.

The place is far away from the market district of the city H.L.M. Grand-Yoff and she goes there often enough to obtain other types of fish her fellow fish-vendors pass to her on commission.

When she settles to sell and must then leave for the neighbourhood market, she leaves the sale of her products to a vegetable-vendor who shares the stand with her. So she spends much of her day at this place waiting for customers.

When she settles to sell and must then leave for the neighbourhood market, she leaves the sale of her products to a vegetable-vendor who shares the stand with her. So she spends much of her day at this place waiting for customers.

See more details of Astou's working day on the Mundus maris channel: click here.

1) Various projects announced, with corresponding large budgets, have so far not solved the problem of access to ice. Shown here is the example of a project supported by the French Development Agency (AFD) which should have solved this problem but is still at the stage of simple poles rising from the ground in an unfinished construction.

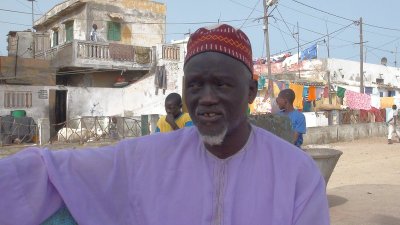

Meeting the President of the artisanal fishermen in Senegal, Kayar

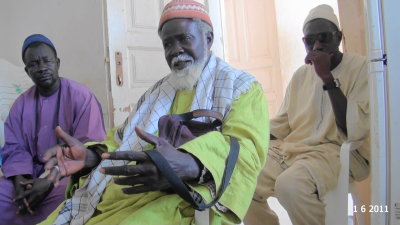

We went Tuesday, June 14, 2011 to Kayar, a traditional fishing village. We have been received by Abdoulaye Gueye DIOP, President of the National Union of Artisanal Fishermen (CNPS) in Senegal.

Abdoulaye Gueye DIOP immediately took us to meet the old fishermen with whom we had a pleasant and fruitful discussion about the project objectives and the interest they bear in Mare Nostrum.

Abdoulaye Gueye DIOP immediately took us to meet the old fishermen with whom we had a pleasant and fruitful discussion about the project objectives and the interest they bear in Mare Nostrum.

An interview was then sought and was an opportunity for us to have a first clear picture of the situation of the fisheries in Kayar and the role that fishermen and other industry leaders play as well as the activities they develop.

Abdoulaye Gueye DIOP begins by noting that the village of Kayar is taken as a reference among all the fishing villages due to the very responsible way in which the fishing activity is organised. Evidence of this conduct is the prohibition by the fishermen of the locality on fishing with monofilament nets (mbalou thiass).

They have even come to serious trouble with the fishermen of Guet-Ndar, another community fishermen living in northern Senegal. It was at the end of these tough fights that the State has issued a decree to prohibit this type of fishing as incompatible with proper management of marine resources. We also note in support of this argument the formal order that line fishermen may not land more than three boxes of fish at a time and purse seine fishermen can not make more than one run per day. The fishermen of Kayar are very respectful to this order. These measures, although indications of the noble concern of Kayar's population for the management of marine resources, also reflect the great difficulties facing those involved in fisheries in general, fishermen in particular. Among these difficulties we may mention:

They have even come to serious trouble with the fishermen of Guet-Ndar, another community fishermen living in northern Senegal. It was at the end of these tough fights that the State has issued a decree to prohibit this type of fishing as incompatible with proper management of marine resources. We also note in support of this argument the formal order that line fishermen may not land more than three boxes of fish at a time and purse seine fishermen can not make more than one run per day. The fishermen of Kayar are very respectful to this order. These measures, although indications of the noble concern of Kayar's population for the management of marine resources, also reflect the great difficulties facing those involved in fisheries in general, fishermen in particular. Among these difficulties we may mention:

-

The limitation of fish landings is a consequence of the lack of conservation means, namely also cold stores.

-

The fisheries agreements signed by the State do not help the effective management of resources. The fishermen say that fish is scarce and not enough for the Senegalese. Therefore, it seems foolish that their government allows foreigners to fish in Senegalese waters. A day without fishing was organised to protest against this and the press conference organised by the CNPS in May 2011 in Dakar was a fresh opportunity for small-scale fishermen to denounce these decisions implemented against their interests.

-

The lack of enforcement by the government of regulations imposed on the practice of fishing. The fishermen play their part perfectly, though the state remains inert and continues to show indifference to the problems of a sector that weighs heavily in the economy of this country.

He also expresses a concern in relation to a specific situation in their locality. Kayar is indeed an area where fishing and agriculture are practiced to approximately equal degrees.

He also expresses a concern in relation to a specific situation in their locality. Kayar is indeed an area where fishing and agriculture are practiced to approximately equal degrees.

The concern is associated with the fear that their village could lose its classification as traditional fishing village, if the fishery would no more pull its weight and that agriculture is seen and taken as a good alternative. Many facts point in this direction:

-

The deplorable condition of the fishermen, when they are no longer able to practice, and the fact that their heirs are not well motivated to continue the activity.

-

The depletion of fish combined with very low capacity of the locality to ensure comprehensive education of the children is an indication for a possible dominance of agriculture as main activity of Kayar, thereby losing its capacity as traditional fishing village - a village where fishing is just a lucrative business, but no longer rather a system, a system where every part of the population is aware of the role it must play for its sustainability.

The depletion of fish combined with very low capacity of the locality to ensure comprehensive education of the children is an indication for a possible dominance of agriculture as main activity of Kayar, thereby losing its capacity as traditional fishing village - a village where fishing is just a lucrative business, but no longer rather a system, a system where every part of the population is aware of the role it must play for its sustainability.

The fishermen demand that the State gets down to more concrete accomplishments and does not spend huge sums of money on seminars, after which their situation does not improve even a jota. Abdoulaye Gueye DIOP also calls for an initiative and its support so that fishermen enjoy social security. He ends the interview by calling on all small-scale fishermen to unite so that all the objectives of the CNPS are achieved, namely improving the living conditions of fishermen and working towards better management of marine resources.

Meeting Ndeye DIENG, President of the CNPS women micro fish vendors

Following our interview with Mr. DIOP, President of CNPS, we went to meet another important person in the fishery. She is Ms. Ndeye DIENG, micro fishmonger and Secretary General of CNPS and President of the female cell. Like almost all of the women in Kayar, she is active fish processing. The main varieties of fishery products are smoked fish, dried fish and fermented, salted and dried fish. The site on which they carry out the fish curing and drying has been built and equipped by the Japanese Cooperation in 2002 (see picture below). Only after our interview with her were we able to visit the site to see for ourselves what we had spoken about concerning their activities. We saw that the installations seemed ill-adapted to the specific requirements of the women and were not used.

Following our interview with Mr. DIOP, President of CNPS, we went to meet another important person in the fishery. She is Ms. Ndeye DIENG, micro fishmonger and Secretary General of CNPS and President of the female cell. Like almost all of the women in Kayar, she is active fish processing. The main varieties of fishery products are smoked fish, dried fish and fermented, salted and dried fish. The site on which they carry out the fish curing and drying has been built and equipped by the Japanese Cooperation in 2002 (see picture below). Only after our interview with her were we able to visit the site to see for ourselves what we had spoken about concerning their activities. We saw that the installations seemed ill-adapted to the specific requirements of the women and were not used.

Together with other women with whom she shares this vast site, Ndeye DIENG told us about the severe conditions which they experience and which are mainly due to a lack of means and other complementary support for the development of fish processing and marketing. The difficulties are:

Together with other women with whom she shares this vast site, Ndeye DIENG told us about the severe conditions which they experience and which are mainly due to a lack of means and other complementary support for the development of fish processing and marketing. The difficulties are:

-

Lack of fish is a big problem. The women criticise the fisheries agreements with foreign vessels allowing these to catch what little fish is left in the waters of Kayar.

-

The deterioration of the kilns and drying rags which they use normally for the processing is forcing them to grill the fish under very rudimentary conditions on the ground burning straw.

-

The distance to markets on which they can sell their products.

The distance to markets on which they can sell their products. -

The lack of conservation and distribution of their products that are popular, but not sufficiently valued. They told us that this type of product is particularly popular with the Togolese, who are very fond of it and come to get it in Kayar at very low prices, then go back to Togo to resell it. They sometimes sell processed fish on credit to Togo and it happens that they are not paid in the end. The reason for taking this risk is that if they can not sell their perishable products in good time, they then see them rot in their hands.

Therefore, the women of Kayar had endorsed an initiative that had enabled them to be trained so that they can read and write and thus be better equipped to carry forward their activities successfully. This training was supported by the French port city of Lorient.

Therefore, the women of Kayar had endorsed an initiative that had enabled them to be trained so that they can read and write and thus be better equipped to carry forward their activities successfully. This training was supported by the French port city of Lorient.

The women request further support for the development of their business and for promoting market access of their products.

Click here for a slide show about the meeting.

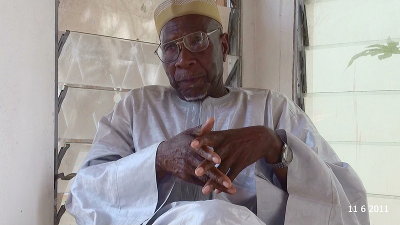

Meeting Abibou Diop, Principal of the CEM Kayar

The interview with women processors was preceded by a visit to the mid-level school (CEM) in Kayar. The CEM Kayar is the main institution of the community. It is located at the entrance of the village and at first glance we see that the infrastructure needed by any institution are not all available, despite the enormous space that was allocated for this purpose. This is what Mr. Abibou DIOP, Principal of the CEM, says and with whom we have had a rich conversation. He made a brief presentation of the CEM Kayar, which has been involved in many initiatives that are consistent with the protection of the environment in general and in particular the marine ecosystem, including through participation in the activities of Mundus maris since quite some time.

The interview with women processors was preceded by a visit to the mid-level school (CEM) in Kayar. The CEM Kayar is the main institution of the community. It is located at the entrance of the village and at first glance we see that the infrastructure needed by any institution are not all available, despite the enormous space that was allocated for this purpose. This is what Mr. Abibou DIOP, Principal of the CEM, says and with whom we have had a rich conversation. He made a brief presentation of the CEM Kayar, which has been involved in many initiatives that are consistent with the protection of the environment in general and in particular the marine ecosystem, including through participation in the activities of Mundus maris since quite some time.

He reiterated his full commitment to the project Mare Nostrum, which he sees as a good opportunity to give a breath of fresh air to a vanishing culture. He also made interesting proposals in order to achieve this purpose.

He suggested the creation of a well-equipped research, training and documentation centre that would serve as the platform for environmental education and would also be a focal point to defend and promote cultural heritage.

He suggested the creation of a well-equipped research, training and documentation centre that would serve as the platform for environmental education and would also be a focal point to defend and promote cultural heritage.

He then explained that prior to the creation of such infrastructure training of qualified personnel would be required to ensure its sustainability.

He also suggests to seek the support of state authorities and of NGOs of all kinds who have at heart the training and research for this institution to give shape to the every good idea and to achieve its main objective, that is, spreading the message of the essential protection and management of aquatic ecosystems.

Click here for a video sequence of the conversation.

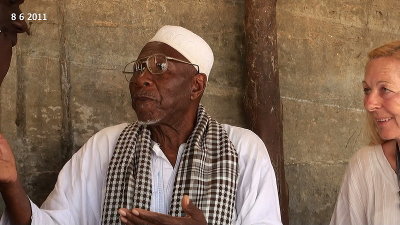

Malick Gueye: An old fisherman from Saint-Louis with rich experience and an open mind

90 years of age today, Malick Gueye is a fisherman from the traditional village of Guet Ndar in the (north) region of St. Louis. What strikes most about this fisherman is his rich path lined with a very young spirit that belies his 90 years.

90 years of age today, Malick Gueye is a fisherman from the traditional village of Guet Ndar in the (north) region of St. Louis. What strikes most about this fisherman is his rich path lined with a very young spirit that belies his 90 years.

During his long life, this fisherman has accumulated a wealth of experience, to mention only the following:

Before independence, Malick was one of the Senegalese pressed by force into the French colonial army that led him to Algeria during World War II;

-

In 1960, the year of the independence of Senegal, the government of Benin approached the government of Senegal to seek an exchange of Senegalese fishermen with a view to assisting in the training of fishermen in Benin. Malick was one of four fishermen selected from Senegal. During two years in Benin, they were able to pass on to the Beninese fishermen the specific expertise in the line fishing, one of the techniques that requires most knowledge and experience. Happy about the work of four Senegalese fishermen on their return to Senegal, the President of Benin then came into their place of origin to St. Louis to congratulate them. But the thing to remember is that from all the fishermen who lived through that experience, Malick is the only one still alive;

He is the pioneer and founding member of the National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen in Senegal (CNPS), the first traditional fishermen's union to have been born in a sector as informal as artisanal fisheries. The foundation of the CNPS in 1987 by Malick GUEYE and other co-founders has been facilitated by the NGO specialised in fisheries, CREDETIP, especially the head and founder of this institution, Mr Aliou SALL. He is from the village of Hann-Pêcheurs and has studied social anthropology in Europe. In the late 1980s to late 1990s, Malick GUEYE has traveled internationally for the emergence and consolidation of a global network of solidarity between the peoples linked by a common maritime culture. Thus, he visited several fishing organisations: in Europe, in France, Guilvinec and Loctudy in Britanny, in Canada, the union called UPM in the Maritime Region in New Brunswick, in Asia the fishermen's unions of Kerala in India and many other communities in Sri Lanka;

He is the pioneer and founding member of the National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen in Senegal (CNPS), the first traditional fishermen's union to have been born in a sector as informal as artisanal fisheries. The foundation of the CNPS in 1987 by Malick GUEYE and other co-founders has been facilitated by the NGO specialised in fisheries, CREDETIP, especially the head and founder of this institution, Mr Aliou SALL. He is from the village of Hann-Pêcheurs and has studied social anthropology in Europe. In the late 1980s to late 1990s, Malick GUEYE has traveled internationally for the emergence and consolidation of a global network of solidarity between the peoples linked by a common maritime culture. Thus, he visited several fishing organisations: in Europe, in France, Guilvinec and Loctudy in Britanny, in Canada, the union called UPM in the Maritime Region in New Brunswick, in Asia the fishermen's unions of Kerala in India and many other communities in Sri Lanka; Starting in the 1990s, he initiated and established a framework within the CNPS for Muslim-Christian dialogue: this initiative has for years created a reconciliation between the union of traditional fishermen and the Catholic Church in Senegal, which has always expressed its support for the artisanal fishing communities. It should be worth mentioning that these fishing communities are composed of at least 75 to 80% of Muslims. It is because of the exemplary work done by the fisherman with the Catholic Church in Senegal for ecumenism that the CNPS has been one of the few organisations in the informal sector to be invited to meet Pope John Paul II in his unique visit to Senegal;

Starting in the 1990s, he initiated and established a framework within the CNPS for Muslim-Christian dialogue: this initiative has for years created a reconciliation between the union of traditional fishermen and the Catholic Church in Senegal, which has always expressed its support for the artisanal fishing communities. It should be worth mentioning that these fishing communities are composed of at least 75 to 80% of Muslims. It is because of the exemplary work done by the fisherman with the Catholic Church in Senegal for ecumenism that the CNPS has been one of the few organisations in the informal sector to be invited to meet Pope John Paul II in his unique visit to Senegal;- Finally, Malick GUEYE is now one of the custodians of the knowledge of Qur'an and performs the duties of a teacher, as a scholar of the Qur'an, and imam in every community where he goes in his various travels between Senegal, Gambia and Mauritania. It should be noted that these 90 years had no impact on his mobility and his trips to Gambia and Mauritania, two neighboring countries of Senegal, where he has a lot of his offspring who emigrate during much of year;

With regard to its openness, while being a strong advocate of morality and decent behaviour in society, Malick impresses with his open-mindedness through:

With regard to its openness, while being a strong advocate of morality and decent behaviour in society, Malick impresses with his open-mindedness through:

-

His position against a religious fatalism which is likely to close our eyes to the scandal that threatens the ecology of our planet for very short-term interests of human beings. Malick GUEYE has shown us with specific passages of the Qur'an that Islam has a clear position against the waste of resources provided by nature;

-

His views are very clear about the religious fundamentalism which he sees as a misinterpretation of the fundamental principles of Islam. According to him, if there is something to which Islam attaches paramount importance, it is the peace between humans in the great respect for the diversity of their religious beliefs.

- To see a diaporama about Malick GUEYE on the Mundus maris channel, click here.

Saint Louis - the last stage of our research in June - an emblematic place

St. Louis was the last stage of our research in June - and it seemed to me that the varied and intense experiences of this month - had begun to flow together in a river that can not wait to unite with the sea, where correlations are waiting in the waves to jump into the transparent air.

For three days we were there - and every day we crossed the bridge to the majestic and generously landscaped history of St. Louis to reach Guet N'dar, to pursue our research. Here few white men get lost here - but we could enter freely because we were accompanied by one of their sons (Aliou Sall) who is committed to the fishermen in Senegal since he returned from his studies in Switzerland - now more than twenty years ago. That was why the doors for us the doors turned out to be open, in a way that on the door step, we have been transformed from a foreigner to a friend.

Every time I had to stop a while in the middle of the bridge to watch the banks of Saint Louis on one side and Guet N'dar on the other side. And with every long look this place has become more and more of a metaphor for the collision of cultures - even if the time of colonialism is past: the "other side" still has no opportunity to move out geographically – at the end of the bank of fine sand, the sea spells the stop on one side and the river on the other. And the bridge, so short, between St. Louis, a tourist attraction, and Guet N'dar, the vital founding village - seems to offer no way to reconcile these two worlds.

Every time I had to stop a while in the middle of the bridge to watch the banks of Saint Louis on one side and Guet N'dar on the other side. And with every long look this place has become more and more of a metaphor for the collision of cultures - even if the time of colonialism is past: the "other side" still has no opportunity to move out geographically – at the end of the bank of fine sand, the sea spells the stop on one side and the river on the other. And the bridge, so short, between St. Louis, a tourist attraction, and Guet N'dar, the vital founding village - seems to offer no way to reconcile these two worlds.

It was in St. Louis that even the meetings had taken an emblematic character, mainly caused by the incredibly dense population of the traditional village in which at every step, each entry and stay in a house the social pressure is palpable. Again and again arose the question of the dignity of the people - even in the poor households there was a shine that had led the perceptions towards substantial things. And there can be no doubt that this is rooted in their culture, which gives them the strength to endure social pressure with dignity. But how long can this work? We know that living conditions are not allowed to go below a certain limit.

The meetings in St. Louis were impressive, even if basically we had not discovered entirely new problems or other conditions. We only had the chance to hear many representative and very strong voices, which led to the creation of an fuller image of diverse views, already heard before.

The meetings in St. Louis were impressive, even if basically we had not discovered entirely new problems or other conditions. We only had the chance to hear many representative and very strong voices, which led to the creation of an fuller image of diverse views, already heard before.

In addition, we developed an understanding that it is not modernity itself that threatens an ancient culture - as long as modernity does not threaten the tradition, vitally present in the culture of fishermen and the women working in the fisheries sector. It is rather the known effects of globalisation or - as it is now on everyone's lips - the globalisation that disrupt the established and proven rules in the cultural, social and economic fabric of fishing communities. Due to the reduction of inputs (fish resources), but also the fact that more and more fishing areas are granted to investors, not just foreigners, alienation is spreading - first at the economic level - with the potential to grow in the social and cultural fabric.

"The poor are tired" - these are the words of the wise old fisherman Malick Gueye - and what that means, we are witnessing in countries of the Maghreb, where one after another people started to rebel.

"The poor are tired" - these are the words of the wise old fisherman Malick Gueye - and what that means, we are witnessing in countries of the Maghreb, where one after another people started to rebel.

Malick taught me that in Africa there is an age to speak, an age where the words carry weight, one where they scold, one where they mollify, one where they scream, mourn, soothe. And one where they are furious ...

Awa SEYE - National President of CNPS Women's cells - fish processing operator and midwife. CNPS is the National Collective of Fishermen in Senegal. She offered hospitality and generously shared experiences about the many challenges and successes of her life.

Read on to get to know Awa SEYE and click here for a slide show on her living conditions as she narrates the many challenges of her life in Guet N'dar.

Awa SEYE: Life of a woman, rich in experience and marked by a tireless commitment to her own community and those of the coast

Awa, now in her 60s, is a woman from the traditional fishing village of Guet N'dar in northern Senegal. Like all women from traditional fishing families - especially in this village of Guet N'dar with its surviving rich cultural heritage - she is responsible for the marketing of products landed by the boat owned by the family. She also has, with his two sisters, a small space on the fish processing site called "Sine". The three take turns to process fresh fish into "braised" or "dried-salted" fishery products. The raw material may be a surplus of landings of their family boat or just the products purchased elsewhere. Even in 2011, we see that the processing sites, despite the preponderance of women who are the main actors, lack basic facilities leaving them almost in similar conditions to before independence in the 60s.

Awa, now in her 60s, is a woman from the traditional fishing village of Guet N'dar in northern Senegal. Like all women from traditional fishing families - especially in this village of Guet N'dar with its surviving rich cultural heritage - she is responsible for the marketing of products landed by the boat owned by the family. She also has, with his two sisters, a small space on the fish processing site called "Sine". The three take turns to process fresh fish into "braised" or "dried-salted" fishery products. The raw material may be a surplus of landings of their family boat or just the products purchased elsewhere. Even in 2011, we see that the processing sites, despite the preponderance of women who are the main actors, lack basic facilities leaving them almost in similar conditions to before independence in the 60s.

If Awa looks like other women in fisheries, she has a trajectory in life that is specific for her in many ways. This singularity is based on her experiences, but also her commitment that is not only unusual for women, but also for fishing communities in Senegal in general. Without being exhaustive, some of her achievements are mentioned here.

If Awa looks like other women in fisheries, she has a trajectory in life that is specific for her in many ways. This singularity is based on her experiences, but also her commitment that is not only unusual for women, but also for fishing communities in Senegal in general. Without being exhaustive, some of her achievements are mentioned here.

First, this woman has become the first and only home birth attendant (called matron) recognised by the official medical and health authorities of the country, from the 80's. This passion or mission did not fall from the sky. Living in a community where many deaths are recorded (mothers and newborns during childbirth), Awa herself has had 4 stillborn children. The fishing community is very Islamised and the loss of life at birth was accepted as divine will. As Astou, the woman met in Yoff and practicing the fish trade in the richer areas of Dakar, Awa also sold fish in the rich part of the city of St. Louis still characterised by the colonial-style houses.

Thus, she met a medical doctor at the hospital, who lived there and with whom she had a tacit but long-standing contract – to ensure fish delivery to his house. The doctor was very touched by the number of children Awa had lost. He offered her training as a midwife so she could help in return the wider community. Thus, for 10 years since 1985, Awa attended to large numbers of women giving birth in her living room, which is 5m by 3m. This was followed by a drastic reduction of deaths in that, once she meets the limits of her assistance, the medical doctors take over. Because she has saved many lives, she is one of the people who have the largest numbers of homonyms in the same place: many of the saved babies are named after her in their birth register, a kind of reward from the grateful and relieved parents. Her commitment and work to stem the scourge of deaths during childbirth became even more successful with the construction of a ward for maternal and child health, where she attends to delivering women and has trained girls with whom she also provides an important training component on HIV in a fishing community characterised by migration in West Africa.

Thus, she met a medical doctor at the hospital, who lived there and with whom she had a tacit but long-standing contract – to ensure fish delivery to his house. The doctor was very touched by the number of children Awa had lost. He offered her training as a midwife so she could help in return the wider community. Thus, for 10 years since 1985, Awa attended to large numbers of women giving birth in her living room, which is 5m by 3m. This was followed by a drastic reduction of deaths in that, once she meets the limits of her assistance, the medical doctors take over. Because she has saved many lives, she is one of the people who have the largest numbers of homonyms in the same place: many of the saved babies are named after her in their birth register, a kind of reward from the grateful and relieved parents. Her commitment and work to stem the scourge of deaths during childbirth became even more successful with the construction of a ward for maternal and child health, where she attends to delivering women and has trained girls with whom she also provides an important training component on HIV in a fishing community characterised by migration in West Africa.

S econd, Awa symbolises the internal struggle of women within an organisation for their representation in decision-making. It is thanks to her that women occupy executive positions in the National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen of Senegal (CNPS). She is not only a member in the national executive, but fought for the establishment of a national women's chapter in the CNPS which she now chairs. Several articles were devoted to her referring to ".... A movement within a movement - Yemaya ICSF."

econd, Awa symbolises the internal struggle of women within an organisation for their representation in decision-making. It is thanks to her that women occupy executive positions in the National Collective of Artisanal Fishermen of Senegal (CNPS). She is not only a member in the national executive, but fought for the establishment of a national women's chapter in the CNPS which she now chairs. Several articles were devoted to her referring to ".... A movement within a movement - Yemaya ICSF."

And lastly, Awa has been a force in the piece of land called Tongue of Barbary, in the real conflict over space between fishing and seaside tourism. In the area coveted by tourists, when the village of Guet N'dar faces a problem of space, Awa has awakened the consciousness of women whose access rights to land - if only for the needs processing activities - were questioned. Thus, with their group of women, they prevailed over the City Council to not only for having space to work but also to benefit from land registration in their name with a view to extending the present village where density per km2 is one of the highest in the world.

Her commitment to fight to preserve the right of access to land for women explains why the CREDETIP (a Senegalese fishing NGO) has always valued the experience of Awa in the various workshops the NGO that has conducted in Senegal on the theme of the difficult cohabitation between the fishing and tourism, this way sharing Awa's experience with women in other areas under the threat of land expropriation in favour of tourism.

Her commitment to fight to preserve the right of access to land for women explains why the CREDETIP (a Senegalese fishing NGO) has always valued the experience of Awa in the various workshops the NGO that has conducted in Senegal on the theme of the difficult cohabitation between the fishing and tourism, this way sharing Awa's experience with women in other areas under the threat of land expropriation in favour of tourism.

In the following, a few more pictures give an impression of the extremely rudimentary and cramped conditions under which the women in Guet N'dar have to go about their fish processing business. Click here for a more comprehensive slide show on their working conditions.