Mundus maris panel at the VII MARE Conference of the People of the Sea titled 'Maritime futures', Amsterdam 25-28 June 2013

This panel organised by Mundus maris at the VII MARE Conference in Amsterdam explored the coping strategies of artisanal fisheries in different parts of the world as they try to retain some of their traditions and social control over economic actors with their role in a globalised market of fisheries products, but also the increasing competition for access to coastal space with tourism and other developments.

Two countries/regions were discussed in a comparative manner to teeth out local specifics from global trends which could inform policy: Senegal in West Africa and the Philippines in Southeast Asia. Underlying the exploration were results from a quantitative reconstruction of catches of the small scale fisheries in both countries as part of the global effort of the Sea Around Us Project, which are a contribution to rectifying widespread misled perceptions of the marginality of ‘traditional’ or artisanal fisheries.

This was enriched by video footage on the what the key actors themselves have to say and qualitative analysis of the strategies deployed by artisanal fisheries to maintain or regain control over their ability to shape alternative futures to industrial and other externally defined development models, largely based on Mundus maris field work.

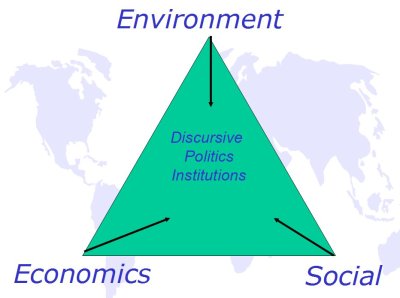

The panel chair, Cornelia E. Nauen, introduced the topic and outlined the ambition to advance in more robust understanding of often complex local situations. The lense of sustainability principles - economics, environment and social issues - is put forward for an analysis of how once traditional fisheries cope in the context of often globalised markets. Ecological and economic perspectives tend to be better researched than social issues.

While different social actors and different disciplines of scientific study approach the issues from a wide range of perspectives, this framework allows to focus on key dimensions and how they interact. The trade-offs between them are shaped in the political process of discursive politics and in the institutions. When one dimension is strongly favoured at the expense of the others the system is unlikely to be sustainable.

This often means that the choice does not fall for the best technical solution in either direction. The second-best technical solution may be more compatible with social organisation and affordable. The concrete balance will reflect local conditions.

With that framing, Deng Palomares of the Sea Around Us Project at the Fisheries Centre of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, set out her talk titled "Artisanal fisheries navigating between tradition and modernity: A short history of subsistence gleaning in Mabini, Batangas, Philippines" with a short video about the people in the study sites.

These had answered structured questionnaires and entertained group discussions with the scientists carrying out this study as part of a larger research project.

Key findings can be summarised as follows:

Catch by gleaning forms a major part of subsistence and municipal fisheries especially in developing countries, but such landings are unreported.

In this contribution, Deng Palomares and her fellow researchers from the FishBase Information and Research Group (FIN), J.C. Espedido, V.A. Parducho, M.P. Saniano, L.P. Urriquia, P.M.S. Yap, attempted to construct a historical overview of gleaning in 10 coastal barangays in Mabini, Batangas.

This is part of wider efforts to reconstruct catches from all types of fishing and harvesting, many of which never get recorded. As a result, national statistics tend to paint an unreliable picture for managers, investors and the interested public.

Their interviews with 111 fishers, 10-84 years of age, indicate a general decreasing trend over 8 decades in gleaned catch, from an average of 2-2.5kg/gleaner and hour prior to the 1950s to 0.5kg in the 2000s. Furthermore, the distance that fishers needed to walk while gathering edible seafood has increased from about 0.5m to about 30m from the shoreline.

That is, they would have gathered a sizeable amount of edible seafood in a 1sqm area during the 1950s (possibly reaching 5kg per gleaner and hour), 20% of which would have been consumed by the family and 80% shared with neighbours or relatives.

Now, they would need to walk as far as 30 m from the shoreline to be lucky to get at least 500g of edible seafood, which would only be enough to feed one family at most for a couple of days. The catch by gleaning, notably in the 1950s and 1960s, did not contribute much to what was sold, rather, the sole purpose of gleaning then was for subsistence, either by the family or by the community as a whole. Gleaning has now been reduced to opportunistic gathering often for the purpose of selling (notably seashells), because there isn’t much left to glean.

Though still of fundamental value to a coastal community, gleaning evolved from being a survival resource to a luxury recreational activity in the last 60 years. We insert a caveat though that this story is not a general trend in most Philippine coastal areas where poverty among fisher communities reign. Click here to see the slides of the talk.

Dyhia Belhabib, also of the Sea Around Us Project, followed on with her paper "The taste of denial in Senegal has driven fisheries to a dead end". Infact, as a result of wide-ranging research along the West African coast, where local small-scale fishers find it hard to resist the competitive pressure of the Senegalese long-distance boats and crews, she retitled her talk "Need or Greed?" to cast light beyond the often stated appearances.

In detailed research in Senegal and neighbouring countries over the last at least two years, she pieced together the catch reconstructions, which gain acceptance after initial denial by authorities and researchers alike. Her findings are summarised as follows:

Exploited marine fish species in Senegal are relatively abundant, and Senegalese fisheries generate a high economic value for local communities. These fisheries are dominated by significant number of Distant Water Fleets and an alarming increase in artisanal effort.

The extent of impact of artisanal fisheries is as poorly known as that of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) industrial fishing. The former relies on official surveys and fishers reports, while the latter was constantly denied in the past. Large and frequent migrations of Senegalese artisanal fishers, under-estimation of fishing effort and increasing, documented conflicts over fisheries suggest that officially reported catch data do not reflect reality.

A thorough literature review, experts and industry consultations were used to reconstruct Senegalese fisheries data. Official national data were compared to the data supplied to FAO and adjusted from 1950 to 2010. Reported and missing sectors, including artisanal catches within and outside Senegalese waters, non-commercial sectors, and industrial catches by the legal and illegal fleets, were re-assessed. Impacts of the intensive illegal fishing activities on artisanal fisheries and the economy were investigated.

Results showed strong under-reporting ranging from four times of the official data in the past to 1.55 times recently. Artisanal catches were responsible for half of total extractions in the last 20 years compared to around 80% officially. That means industrial fleets took a lot more than reported. Additionally, while catches by migrant fishers increased drastically, artisanal catches from Senegalese waters decreased despite an increasing effort. This suggests strong over-capacity. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) catches, which were worth around US$ 300 Million annually, transhipped, hidden and discarded result in strong economic loss and the exile of a large segment of artisanal fisheries out of Senegal. This is a strategy to compensate for the loss driven by the need for food and the greed for higher value. Click here for the powerpoint presentation.

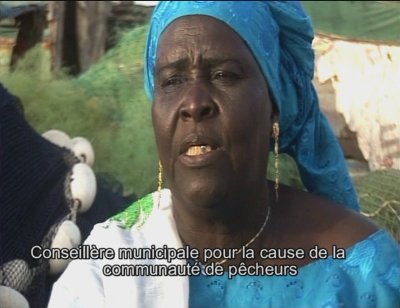

Following on from this wake-up call reassessing and quantifying the production, Aliou Sall, a socio-anthropologist from Senegal, elaborated on the social dimension of these developments. He also discussed the seemingly paradoxical situation that the artisanal fishers were barely constrained by official rules and regulations, but still experienced an erosion of their political clout and of livelihoods.

The image of deep crisis of small-scale fisheries in Senegal complement the quantitative assessments by economists and biologists. Based on interviews with representatives of fish worker’s trade union and/ or local association and qualitative field observations these past years, other tools for 'making sense' of the crisis have been developed so as to be more accessible to the social actors themselves.

The crisis in the fisheries is not only manifest in terms of 'worsening of their socio economic conditions', because globalisation has impacted significantly on their bargaining power both with policy makers and economic actors that dictate the rules of the international and local markets.

Aliou Sall discussed how these traditional fishing communities cope. This implies not only preserving or restoring 'an economically and environmentally viable' activity, but also a 'way of living'. Fishers, fishmongers and women fish processors are constantly adapting their strategies to this end. The brutal strains of globalisation have impacted women involved in fisheries selectively to the extent that we can talk nowadays about 'the feminisation of poverty in the small scale fisheries'.

Their traditional roles of (often hidden) investors and managers in artisanal fisheries, are being undermined through the influx of external capital not subject to social control and a general trend to overcapitalisation. The relentless expansion of all segments in the fisheries has deeply degraded once productive marine ecosystems and disrupted respect for earlier restraint on resource extraction in traditional social settings.

The author argues for addressing the crisis through more participatory and transsectoral approaches. These forms of governance should be based on strong democratic institutions with potential to exit the rush to the bottom.

This should rescue what is best within traditional beliefs and practices and modernity. Suggestions are put forward for necessary transitions towards sustainable governance. Starting points could be improvements of habitats on the shores, which would not only benefit the fishing communities themselves, but others, including municipalities, tourism operators and other citizens. Collectively negotiated and implemented measures such as clean beaches would also build trust among different stakeholders currently engaging very little with one another. Click here to see the powerpoint presentation.

Following on from the presentations, the other participants in the audience put forward numerous questions and comments, many specifically tailored e.g. to the developments in Senegal in the last two to three decades as several others had worked there before. The interest was palpable and kept everybody in the exchange well into the evening cocktail.

Older participants in the room asked whether the new title of the catch reconstruction in Senegal "Need or Greed?" was not too polarising and value-laden. However, Dyhia Belhabib stood by the sharpening of the appreciation as a result of the data collated. She suggested that action was needed to draw practical conclusions from the new quantification and bring the fisheries back in line with the rules and an exploitation level compatible with regenerative capabilities of the marine ecosystem.

There was consensus that social advances, not only in Senegal, but also elsewhere, would be easier, if lost productivity of the resource system would be restored. Bringing everybody to the table so as to build the political will and support for drastic adjustments is a tall order. In particular, how to reign in the boom and bust cycle of international markets, which had transformational effects on the societies and ecosystems alike?

Riding the tide clearly gave a raw deal to all but a few. So strengthening efforts to rebuild marine ecosystems, reigning in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and promoting a better integration of the social dimension into the equation came out as the most promising avenues to pursue. It was, however, also clear that robust solutions would have to be build around the articulation of these general needs in each specific context, whether it be Batangas in the Philippines, Senegal or other countries or regions.

Lots of more research effort is needed here, preferably research done in modes that engage critically with the social actors so as to make it most readily useful for the social and political negotiating process.