Studium oecologicum is a core programme in support of sustainability organised by a group of student representatives at the University of Potsdam for students from any branch of studies. Cornelia E Nauen of Mundus maris was invited in this context to give a talk on 19 November 2021 on the meaning of overfishing and its relation to the globally accepted Sustainable Development Goals. Overfishing is often associated with unsustainable or even criminal practices and has far-reaching negative effects on marine biodiversity, the capacity of the ocean and its ecosystems to cope with climate change, our seafood supplies and on the lives of people depending on a healthy ocean in artisanal fisheries.

Studium oecologicum is a core programme in support of sustainability organised by a group of student representatives at the University of Potsdam for students from any branch of studies. Cornelia E Nauen of Mundus maris was invited in this context to give a talk on 19 November 2021 on the meaning of overfishing and its relation to the globally accepted Sustainable Development Goals. Overfishing is often associated with unsustainable or even criminal practices and has far-reaching negative effects on marine biodiversity, the capacity of the ocean and its ecosystems to cope with climate change, our seafood supplies and on the lives of people depending on a healthy ocean in artisanal fisheries.

The talk was recorded (in German) to allow more students to listen in if they had missed the original lecture and Q&A session. The powerpoint presentation (in German) is available by clicking on the link. Here are just a few highlights.

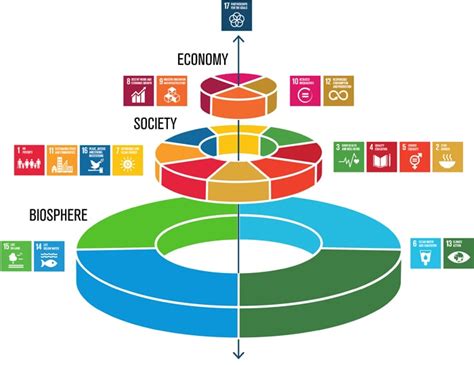

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015 can be understood as layers sustaining our lives and civilisations. The bottom layer or foundation of the biosphere is composed of SDGs 6 (Clean water and sanitation), 13 (Climate action), 14 (Life under water) and 15 (Life on land).

The SDGs aiming at sustainable societies are the following: 1 (No poverty), 2 (Zero hunger), 3 (Good health and well-being), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 7 (Affordable and clean energy), 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), 16 (Peace, justice and strong institutions).

The SDGs aiming at sustainable societies are the following: 1 (No poverty), 2 (Zero hunger), 3 (Good health and well-being), 4 (Quality education), 5 (Gender equality), 7 (Affordable and clean energy), 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), 16 (Peace, justice and strong institutions).

The third layer of SDGs focuses on making the economy work for sustainable societies by focussing on SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth), 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure), 10 (Reduced inequalities) and 12 (Responsible consumption and production).

At the top is SDG 17 recognising that their implementation hinges on Partnerships for the goals and cooperation.

How does overfishing relate to the SDGs? Let's start with some definitions taken from Pauly (1988) (1):

Growth overfishing – catching them too small for achieving maximum sustainable yield (MSY).

Recruitment overfishing – too few young fish recruit into the fisheries because of a decimated parent stock or e.g. degradation of nursery areas (e.g. mangroves...)

Economic overfishing – the level of effort is higher than needed for maximum economic rent (>MSY)

Ecosystem overfishing – changes in species composition and relations in the ecosystem lead to reducing resources (useable by humans) in favour of non-resource species

Malthusian overfishing – too many fishers chasing too few fish (e.g. for lack of alternative livelihoods).

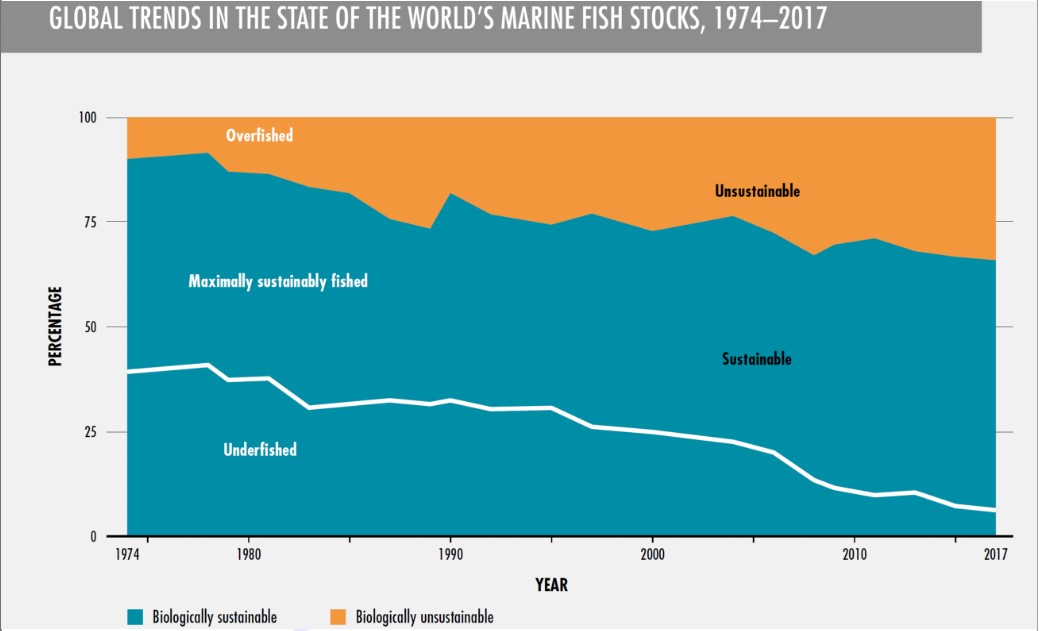

In its last bi-annual State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020 report FAO shows the general trend of stocks of marine fish, the large majority of which are either collapsed or fully exploited. Very few are considered underfished.

In the face of large global catching overcapacities, the inability to exploit untapped resources leads to often aggressive competition and dubious, even illegal practices.

In the face of large global catching overcapacities, the inability to exploit untapped resources leads to often aggressive competition and dubious, even illegal practices.

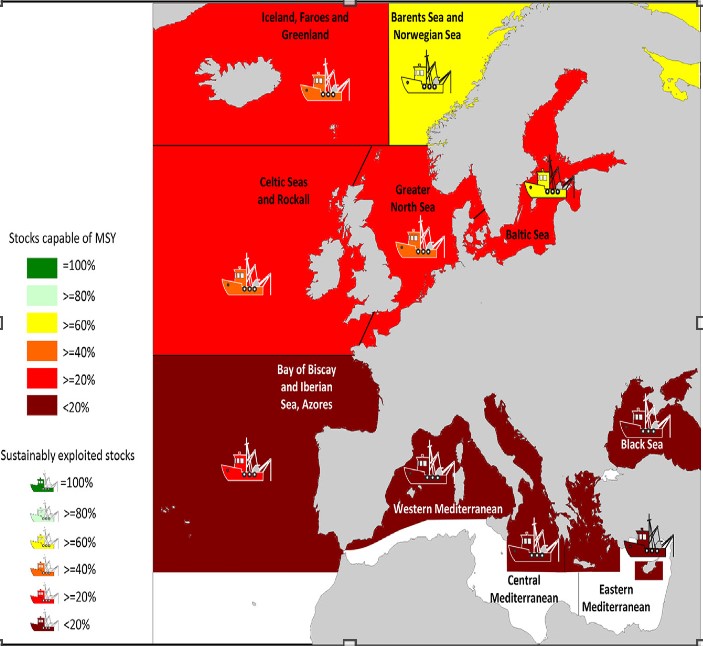

In European waters, Froese and co-authors (2018) concluded that at least 40% of 357 stocks analysed were too heavily fished and had such reduced abundance of adult fish and invertebrates that they could not produced the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) mandated by the reformed European Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).

The overcapacity and overfishing is driven largely by harmful public subsidies, estimated by Sumaila and co-authors (2019) at USD 22.2 billion. China, European Union, USA, Republic of Korea and Japan contribute 58% of these subsidies. Around 85% are directed at industrial operators, port development, fuel for long-distance fleets and other capacity enhancing measures.

Paradoxically, the subsidies paid out by the German government exceed the value of the catches as shown in the Ocean Atlas of the Boell Foundation, but overall in the European Union Spain dished out the highest level of harmful subsidies, while spending very little on beneficial ones (research, management, safety at sea).

Among the greatest victims are marine biodiversity embedded in their ecosystems and men and women in small-scale fisheries who account still for a quarter of global catches. Most of these are high quality products for human consumption. But their livelihoods are undermined by the operations of industrial fleets. These tend to generate high environmental impacts, be it by provoking high discards, habitat destruction or high CO2 emissions or combinations of these factors.

However, subsidy driven overfishing has many more harmful effects as it may be often associated with dubious or outright criminal practices, including fraud, corruption, drugs and arms running, labour abuse and human trafficking. These practices often also mentioned in conjunction with illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing by industrial vessels harm developing countries disproportionately as they tend to suffer from weak monitoring, control and surveillance of their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and poor law enforcement. These few elements illustrate the extent of jeopardy constituted by overfishing to several SGDs.

However, subsidy driven overfishing has many more harmful effects as it may be often associated with dubious or outright criminal practices, including fraud, corruption, drugs and arms running, labour abuse and human trafficking. These practices often also mentioned in conjunction with illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing by industrial vessels harm developing countries disproportionately as they tend to suffer from weak monitoring, control and surveillance of their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and poor law enforcement. These few elements illustrate the extent of jeopardy constituted by overfishing to several SGDs.

The SDGs set concrete targets to come to grips with these challenges. A key demand was for the World Trade Organization to phase out harmful fisheries subsidies by end 2020, a demand which had been on the WTO agenda for 20 years. That deadline was missed, but a broad alliance of civil society organisations, including Mundus maris, is relentlessly putting pressure on the state parties in the negotiation to deliver. The arguments in favour are overwhelming in terms of benefits for a level playing field, resource recovery, responsible management of public funds and social justice to name only the most obvious.

A large number of scientists have called on the WTO to strike the overdue deal at long last. And more are joining after publication in the prestigious journal 'Science'.

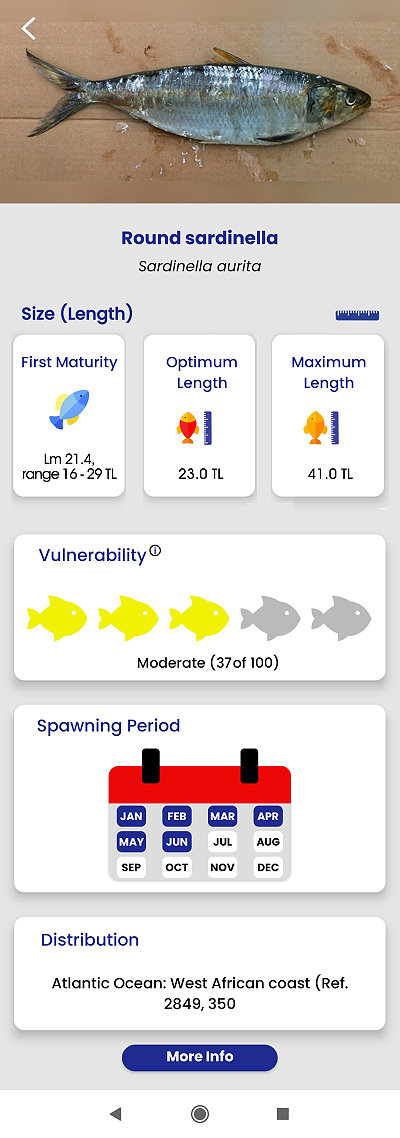

Those more inclined towards hands on action in their daily lives can since October make use of an App we sponsored to show key sustainability indicators of any fish you have a common name in a language in use in your country. You type the name and the country in the FishBase Guide App and you will be shown a picture of the fish, its different common names, valid scientific name and the length at which it will have achieved maturity. You also get the optimum length. That is the length at which the catch is maximised over time. The maximum length recorded will often surprise users as most of the fish in the market tend to be small or perhaps only presented as fillets or even fish sticks in supermarkets.

As in the screen shot to the right, you will also see a visual representation of the vulnerability of the species to overfishing and related types of pressure. Indications of the spawning season, during which species should not be caught, a broad indication of its geographical distribution and a link to the Species Summary Page in FishBase for those interested to know more rounds off the service provided.

The App is more versatile than the fish rulers that were developed for a few countries or regions, such as southern Peru, Senegal and Gambia, Greece or the North Sea and the Baltic. You can call up the information for a large number of species anywhere in the world.

The good news is that the legislation in Europe is prohibiting overfishing, indicates marine and coastal protection zones and encourages responsible practices, opening up opportunities for citizen participation, e.g. by making available a pocket guide with minimum labelling requirements for transparency and potential accountability. The bad news is that enforcement of the rules by politicians and responsible authorities tends to be weak and protected areas don't protect.

So, not only NGOs active in marine protection and species conservation, but also small-scale fishers are taking initiatives to protect vital areas to contribute to restoring a healthy ocean and also safeguard the future of the profession. One such example is the Casa dei Pesci (House of Fish), an underwater museum created with sunk marble sculptures off Talamone on the Tuscan coast in Italy, where Paolo Fanciulli and his supporters are preventing illegal destructive bottom trawling thanks to the sculptures and other obstacles sunk. Their long-standing struggle is creating some results in the form of bigger fish, healthy Posidonia seagrass meadows and returning dolphins and turtles. It's an encouraging sign of what is possible, when good science, engagement of the arts and sustainability criteria are being put into practice with strong citizen support.

Indeed, SDG 17 recognises the need for partnerships and cooperation at all levels, from the local to the global. We all stand to gain.

(1) Pauly, D., 1988. Some definitions of overfishing relevant to coastal zone management in Southeast Asia. Tropical Coastal Area Management, 3(1):14-15.