SWAIMS, the Regional Programme "Support to West Africa Integrated Maritime Security", headquartered in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, focused it's webinar on 31 March 2021 on "Curbing Maritime Insecurity in the Niger Delta". One of the speakers invited in the occasion of this exchange with civil society organisations was Prof. Stella Williams, Vice President of Mundus maris, who spoke on the topic of Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and its effect on small-scale fisheries.

SWAIMS, the Regional Programme "Support to West Africa Integrated Maritime Security", headquartered in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, focused it's webinar on 31 March 2021 on "Curbing Maritime Insecurity in the Niger Delta". One of the speakers invited in the occasion of this exchange with civil society organisations was Prof. Stella Williams, Vice President of Mundus maris, who spoke on the topic of Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and its effect on small-scale fisheries.

SWAIMS covers all 15 countries of the Economic Community of West African States, also known as ECOWAS, which together have a population of more than 350 million people. The project is financially supported by the European Union. Given the currently high incidents of armed robberies and various illicit practices the programme addresses some burning issues in the Gulf of Guinea. The spotlight of this webinar was on the Niger Delta. The agenda is available here.

Mr. Barthélemy Blédé of SWAIMS guided the audience through the programme, explained the background of this webinar and introduced the speakers. Following on from the official welcomes, Nkasi Wodu, Peace Building Programme Manager of the Foundation for Partnerships in the Niger Delta (PIND) spoke about piracy and its root causes. He underscored that piracy was not only a maritime phenomenon, but that it was important to understand its operations in inland waterways and its bases in the hinterland, where hostages taken in marine and coastal waters were usually held for demanding ransom.

He explained that the root causes of piracy were the destruction of agricultural lands and fishing grounds from oil and gas exploration and exploitation that left young people without hope of gaining a living with legitimate work. In such circumstances, which were similar to what was observed in Somalia and other insecurity hotspots, it was easy for criminal organisations to recruit young unemployed and frustrated men for their "business". The effects were felt at many levels:

- disruption of trade, coastal traffice and fishing as a result of high levels of insecurity and resulting increases in cost of water-borne activities and goods,

- fishers were venturing further to escape the pirates with higher risk of life and operational costs

- higher costs of oil and gas operators

- reduced government income from oil and gas exploitation

- reinforcement of other criminal activities, including drug and arms running.

In brief, the entire maritime economy was threatened and violence levels were high. The estimated number of small guns in the hands of privateers had shot up in recent years and was estimated at more than 6 million compared to 0.5 million of the police, coast guard and other public authorities. The connections to organised crime had grown over the years and Nkasi Wodu emphasised that a purely military or policing response would not root out the challenge. He saw opportunities for civil society organisations to work with youths for alternatives, but also stressed that without more just sharing of the wealth of resources in the Niger Delta, it was difficult to imagine peace.

In brief, the entire maritime economy was threatened and violence levels were high. The estimated number of small guns in the hands of privateers had shot up in recent years and was estimated at more than 6 million compared to 0.5 million of the police, coast guard and other public authorities. The connections to organised crime had grown over the years and Nkasi Wodu emphasised that a purely military or policing response would not root out the challenge. He saw opportunities for civil society organisations to work with youths for alternatives, but also stressed that without more just sharing of the wealth of resources in the Niger Delta, it was difficult to imagine peace.

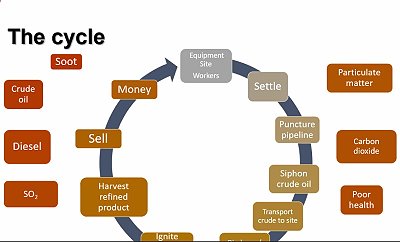

Dr. Ebinimi Joseph Ansa of the Nigerian Institute of Oceanography and Marine Research (NIOMR) in Port Harcourt, eloquently described the cycle of oil theft and its far reaching ripple effects in terms of public health, environmental destruction, climate, government revenue loss and more. She detailed the entire economy that had developed around crude oil theft and its distributed refinement putting products on local markets that were so much cheaper than those from official sources that official kerosene refinement has simply stopped. She identified similar root causes, including corruption, poorly paid law enforcement and widespread poverty as the previous speaker and recommended to address these together with a controlled legalisation of modular refineries to overcome the lawlessness.

Prof. Stella Williams of Mundus maris asbl spoke about illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and it's effect on the numerous people in small-scale fishing communities in Nigeria. She started with an explanation of IUU fishing and about how a composite index of the different dimensions of the problems gets estimated for every country with a coastline on a scale between one and five. Five stands for worst performance.

Source: https://www.iuufishingindex.net

The IUU Fishing Index comprises a suite of 40 indicators, with each indicator related to both a ‘responsibility’ and a ‘type’.

-

Coastal responsibilities relate to a state’s management of its exclusive economic zone.

-

Flag responsibilities are things states should do to manage vessels they flag.

-

Port responsibilities relate to control of fishing activity in ports.

-

‘General’ indicators are those not specific to coastal, flag or port state responsibilities.

Types of indicators relate to vulnerability – the risk of exposure to IUU fishing, prevalence – known or suspected IUU fishing, and response – actions by a state to reduce IUU fishing. Data for the indicators are derived from both secondary sources and expert opinion.

With an overall score of 2.39 Nigeria is ranked 49 out of 152 assessed countries.

Fishing is a major source of livelihoods in Nigeria. According to the FAO, in 2014, 713 000 persons were reported as engaged in inland fisheries with 21% of this total being women as they are known to go fishing. 15% of the total of 764 600 people engaged in other fisheries (marine and coastal) were women in 2014. Women are dominant in postharvest activities. Most of the value generated was from small-scale fishing operations.

In addition to the security issues mentioned in previous talks, IUU fishing, often perpetrated by industrial vessels flying foreign flags, are direct competition for small scale fishers even in coastal marine waters. The drastic recline of marine extractions documented by the Sea Around Us in collaboration with Nigerian scientists since the beginning of the millennium followed on the heels of a steep increase of industrial fishing in addition of what was already a fully developed artisanal fishery.

The negative effects were hardships for the artisans, shortages of small pelagics for traditional processing for coastal and up-country markets, loss of lives and gear for fishers, children dropping out of school and more. Bulk imports of frozen small pelagics by industrial vessels e.g. from Russia and The Netherlands partially compensated for the domestically unmet demand. In the wider Lagos area with a large population and high purchasing power men and women around Makoko Island converted to catfish farming and smoking to find new ways to make a living. While this brings some respite, it may turn out to be a poisoned gift as carnivores like catfish need to be fed high protein feeds. At scale this is expected to exacerbate the shortage of small pelagics for human consumption and a net reduction of food production.

The negative effects were hardships for the artisans, shortages of small pelagics for traditional processing for coastal and up-country markets, loss of lives and gear for fishers, children dropping out of school and more. Bulk imports of frozen small pelagics by industrial vessels e.g. from Russia and The Netherlands partially compensated for the domestically unmet demand. In the wider Lagos area with a large population and high purchasing power men and women around Makoko Island converted to catfish farming and smoking to find new ways to make a living. While this brings some respite, it may turn out to be a poisoned gift as carnivores like catfish need to be fed high protein feeds. At scale this is expected to exacerbate the shortage of small pelagics for human consumption and a net reduction of food production.

Stella summarised some of the key features Mundus maris has identified as often associated with IUU fishing, such as corrupt agents and officials in ports, high levels of activities in a port making it easy to hide illicit landings, an atmosphere of lax rule enforcement, offshore reefer activities and weak monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) at sea. The artisanal fishers and their families are the first to suffer the consequences, but IUU fishing also fosters overfishing and impedes fisheries management as data are scarce and unreliable and investments likely based on erroneous assessments.

She also put forward a series of measures to address the need for positive change, including work towards resource recovery, the implementation of the Voluntary Guidelines to Ensure Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries and of the interdependent Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Measures should entail emphasis on phasing out harmful fisheries subsidies in the World Trade Organization (WTO). While governments had missed the 2020 deadline of target 6 of SDG 14, it was of utmost importance to stop this source of funding overfishing soonest. Investing in people, men and women in artisanal fishing and value chains and strengthening their capacities through such approaches as the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy was crucial to complement the implementation of global commitments. The most recent workshop in Yoff, Senegal, illustrated the positive effects for academy learners despite the adversities generated by the pandemic. In conclusion, Stella invited SWAIMS and other organisations from among the panelists and the audience to collaborate in following up on the diagnoses and suggested action at the centre of the webinar. The slides can be seen here.

Ogbonna Okechukwu Chidi spoke about human trafficking, a particularly hideous practice on the rise, which tended to force young females into domestic service and sex traffic, while young men were primarily forced into hard labour and militias. Nigeria suffered particularly badly from these organised crimes. According to some estimates almost 1.4 million people were victims of such unscrupulous practices. The most promising response would be the four Ps: prevention, protection, prosecution and partnerships.

This memorable webinar finished with a lively Q&A session and closing remarks by the SWAIMS moderator drawing out some lessons for future action and possible collaboration.