Our values influence the rules in our communities

Click here for an important update on the Mare Nostrum Project of Mundus maris

It sounds like a truism, but evolving values and the competing claims for setting the rules affect daily lives and decisions in the fishing communities in very real ways. This is exacerbated by the crisis or near crisis situations in relations to the resource, to urbanisation and the conditions of living space, as well as the difficulties to invest in new and also alternative livelihoods when the economic conditions are worsening.

The Mare Nostrum team, composed of Carla Zickfeld, MN Coordinator, Aliou Sall, local coordinator, and Stefan Karkow, documentalist, has been working through October 2011 in four fishing villages: Hann, Yoff, Kayar and Saint Louis.

The Mare Nostrum team, composed of Carla Zickfeld, MN Coordinator, Aliou Sall, local coordinator, and Stefan Karkow, documentalist, has been working through October 2011 in four fishing villages: Hann, Yoff, Kayar and Saint Louis.

This time, the focus of attention in the villages was on gathering evidence about the belief and value systems of the communities, as they are experienced by the men and women living there. In particular, the interviews summarised in the following short reports bring out the role of the sacred in organising community life and how this affects their relationship with the marine resources and with public rules and policy.

A second line of work involved the planning of future activities with a view to share the challenges of the fishing communities with academics and practioners from outside in search of robust answers to these challenges. Here aesthetic education and practiced international solidarity form the basis of the planning.

In this context, the Goethe Institute in Dakar has accepted to be a partner in the organisation of an international multi-stakeholder conference in May or June 2012, during the forthcoming Biennale Dak'Art 2012. A photo-exhibition by Stefan Karkow should be part of the conference programme and the renowned Senegalese artist Sambalaye DIOP has accepted a role as curator of the exhibition of contemporary artists about the symbolism of the sea. A cultural manifestation is foreseen about the cultural heritage of the traditional fishing communities with dances, songs and poetry of the people of the sea.

All photos in this section by Stefan Karkow.

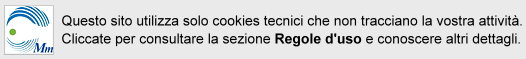

Visit to Boucar FALL: A traditional chief of fishermen in Hann-Pêcheurs and how this inspires us

A real consideration of customary power within public policy could be contributing to the sustainable management of fisheries resources

In traditional communities, the dichotomy between modern and customary power reveals itself as being all but a myth. Boucar FALL is a traditional chief of the fishermen in Hann-Pêcheurs (the fishing village inside the town of Hann). According to Boucar Fall, in the past, governments have always relied on customary power to manage conflicts between citizens, whether in the field of conflict in general or that of the distribution and collective management of natural resources. The traditional leader illustrates this statement through a few examples, without trying to be comprehensive, of course.

In traditional communities, the dichotomy between modern and customary power reveals itself as being all but a myth. Boucar FALL is a traditional chief of the fishermen in Hann-Pêcheurs (the fishing village inside the town of Hann). According to Boucar Fall, in the past, governments have always relied on customary power to manage conflicts between citizens, whether in the field of conflict in general or that of the distribution and collective management of natural resources. The traditional leader illustrates this statement through a few examples, without trying to be comprehensive, of course.

First, despite the existence of courts, the gendarmerie and police that are very competent in their field, conflicts between the inhabitants of Hann, have always been settled at the village level, in the courtyard of the village chief, a responsibility exercised by Boucar FALL. He inherited it from his father, the late Babacar Fall. Still according to Mr. FALL, each time a resident of Hann has a complaint against another at different levels of the gendarmerie or police, the men in uniform return it without delay to the village chief, to find a local solution.

Second, continues the traditional leader, the traditional authorities were traditionally heavily involved in organising the exploitation of natural resources. In the case of fishing for example, both inland and maritime, each fishing area and a resident local chief, who was responsible for fishing in general and at the same time head of the village or community (especially for the camps of migrants). The latter has always been at the head of the local community bodies that were responsible for issues as concrete and related to (i) how the coastal zone should be occupied by the users; and to (ii) institutionalised 'informal' arrangements for regulating access to resources with the well-known practice of the coast of Senegal, who saw the fishermen set up a rotating access system to resources.

Second, continues the traditional leader, the traditional authorities were traditionally heavily involved in organising the exploitation of natural resources. In the case of fishing for example, both inland and maritime, each fishing area and a resident local chief, who was responsible for fishing in general and at the same time head of the village or community (especially for the camps of migrants). The latter has always been at the head of the local community bodies that were responsible for issues as concrete and related to (i) how the coastal zone should be occupied by the users; and to (ii) institutionalised 'informal' arrangements for regulating access to resources with the well-known practice of the coast of Senegal, who saw the fishermen set up a rotating access system to resources.

According to our interlocutor, the role of the customary power in conflict resolution is not new and therefore contemporary with the modern state. He recalls some very striking facts to support his statements to the effect that (i) during the colonial era, the French authorities in office never entered the village without prior notice to the village chief, at the time Boubacar Ndiongue, a native of Walo and founder of the fishing village of Hann (Hann-Pêcheurs). He founded the first quarter of this fishing community, today called Waloga, part of a village that has grown very significantly since. These social mechanisms regulating villagers coexisted with the conventional state rules, are at least taken into account by the modern world and created even a reverse situation: a conflict of competence and authority between the Law and what communities see as their traditional Rights.

According to our interlocutor, the role of the customary power in conflict resolution is not new and therefore contemporary with the modern state. He recalls some very striking facts to support his statements to the effect that (i) during the colonial era, the French authorities in office never entered the village without prior notice to the village chief, at the time Boubacar Ndiongue, a native of Walo and founder of the fishing village of Hann (Hann-Pêcheurs). He founded the first quarter of this fishing community, today called Waloga, part of a village that has grown very significantly since. These social mechanisms regulating villagers coexisted with the conventional state rules, are at least taken into account by the modern world and created even a reverse situation: a conflict of competence and authority between the Law and what communities see as their traditional Rights.

This jurisdictional dispute explains (even if it does not justify) the reluctance of fishing communities to deal with various technical and legal instruments (State Code for Fisheries, different tools promoted by the FAO, etc.), set up by public authorities for the sustainable management of resources. The lack of full adherence to these measures - giving future prospects for the sustainable management of resources - from the very people, who are both prime victims of the resource crisis but also with a share of their responsibility, is largely a crisis a balance between modernity and tradition in the specific area of co-management.

This jurisdictional dispute explains (even if it does not justify) the reluctance of fishing communities to deal with various technical and legal instruments (State Code for Fisheries, different tools promoted by the FAO, etc.), set up by public authorities for the sustainable management of resources. The lack of full adherence to these measures - giving future prospects for the sustainable management of resources - from the very people, who are both prime victims of the resource crisis but also with a share of their responsibility, is largely a crisis a balance between modernity and tradition in the specific area of co-management.

This crisis in the institutional arrangements is becoming acute in the now fashionable modalities imposed from above in the name of co-management. These new arrangements are carried forward by a more or less recent phenomenon of decentralisation, which is gradually supplanting the traditional regulatory bodies. The results will appear in the arrangements between the different sources of values and ways of resolving conflicts and relationships and their ability to prevail in practice.

Fotos by Stefan Karkow.

Conversation with Bacar FALL, fisherman in Hann, President of the landing site

Our impressions: Survival and vitality of the sacred, unconsciously maintained by the fishing community

Our impressions: Survival and vitality of the sacred, unconsciously maintained by the fishing community

Bacar FALL is a fisherman and the president of the Economic Interest Group (EIG) for the management of the landing site of Hann-Pêcheurs.

As part of the present Mare Nostrum mission, which focuses on the "sacred" and how the fishermen themselves are living it, we spoke with him.

The key elements of our conversation with this fisherman can be summarised in three points.

-

First, he placed great emphasis on the fact that the practices of the sacred have changed in form with the constraints of the current environment, in which the fishing community lives. This is due to the fact that urbanisation not allow certain practices anymore, due to promiscuity and population pressure, which affect the intimacy between humans and nature.

First, he placed great emphasis on the fact that the practices of the sacred have changed in form with the constraints of the current environment, in which the fishing community lives. This is due to the fact that urbanisation not allow certain practices anymore, due to promiscuity and population pressure, which affect the intimacy between humans and nature.

- Then he acknowledged that the Islamisation of fishing communities, which has much impact on the animist practices, is a recent phenomenon as far as the peoples of the Sea are concerned.

Finally, he is convinced that the animist practices are not only under threat of disappearing with the new generations, present and future, but that in the current environment, these practices are actually now the past. He puts it down to the influence of the Islamisation of his community, who banished all practices combining a monotheistic religion with animism.

Finally, he is convinced that the animist practices are not only under threat of disappearing with the new generations, present and future, but that in the current environment, these practices are actually now the past. He puts it down to the influence of the Islamisation of his community, who banished all practices combining a monotheistic religion with animism.

This last point is one of the elements, which attracted most of our attention, especially when we compare this with on-going practices in the community of Hann-Pêcheurs.

Hann has many mosques, just like many other communities - showing that Islam is the dominant religion.

Yet, the fact that pirogues are full of talismans for the safety of fishermen and their property indicates a belief in supernatural forces that control their well being and safety, which is still rooted in the fisherfolk's minds.

Yet, the fact that pirogues are full of talismans for the safety of fishermen and their property indicates a belief in supernatural forces that control their well being and safety, which is still rooted in the fisherfolk's minds.

In addition to these practices, one needs to add the spending by fishermen on consultations with marabouts, who are supposed to bless their trip.

View a short video of part of the conversation with him.

Three generations of women give their opinion on the practice of the sacred

The role of women in the continuity against all odds in heavily Islamised communities

We visited the family of Khady Fall, called "Sela", for a special session with the aim to obtain simultaneously the views on the practice of the sacred of women from three generations. We have met Khady Fall, her mother, Coura Diop, and her daughter, Fatou Sarr, in their concession in the village of Hann-Pêcheurs.

We visited the family of Khady Fall, called "Sela", for a special session with the aim to obtain simultaneously the views on the practice of the sacred of women from three generations. We have met Khady Fall, her mother, Coura Diop, and her daughter, Fatou Sarr, in their concession in the village of Hann-Pêcheurs.

As we have stressed in some of our earlier reports, Hann-Pêcheurs is strongly influenced by the importance of the Muslim segment of its population. The presence of Islam has had an impact on the animist practices to the point that men, draped daily in their boubou, rosary in hand, have difficulty in recognising that the practice of the sacred is still present in their homes. We must also understand their attitude to the extent that Islam condemns animist practice and the belief in a supernatural power other than God.

But parallel to this position of the men, attesting and insisting that the practice of the sacred is no longer around, the interview with three generations of women shows how these still believe strongly in these realities. While the forms of expression of these beliefs may vary from one generation to another, there remains a constant: the sacred is not only part of their lives, but also provides them with physical security and insurance for their livelihoods as human beings with multiple needs. Indeed, in front of us these three women from three generations expressed their attachment to the sacred in the following ways:

-

A grandmother, Coura Diop, illustrated through examples that the sacred practices have tangible positive effects on people, who adhere to these beliefs. She compares the breakdown of these practices with the curses some young people live through;

A grandmother, Coura Diop, illustrated through examples that the sacred practices have tangible positive effects on people, who adhere to these beliefs. She compares the breakdown of these practices with the curses some young people live through; -

Khady Fall confirms the fact that in her work these practices are still ongoing in that the women of her generation continue to use the prayers from people known for the special power they hold: the use of those magical repositories of knowledge for success in work or guarding against bad luck. So for her, the women of her generation hang on to this cause. She is more concerned for future generations, who she thinks are too exposed to the potential effects of globalisation, especially with the new communication technologies;

-

Finally, Fatou Sarr, Khady's daughter, aged 36, who has two children: she adopts an attitude demonstrating that she does not question these beliefs so deeply rooted in the fishing families. Indeed, while very much a daughter of this community, she takes full advantage of modern opportunities (use of social networks to communicate with people of her generation) agrees strongly with the fact that, for younger generations "calling into question the tradition, including the belief in the sacred, could be hazardous for the next generation." She insists that not aspects of modernity are to be taken on board.

Finally, Fatou Sarr, Khady's daughter, aged 36, who has two children: she adopts an attitude demonstrating that she does not question these beliefs so deeply rooted in the fishing families. Indeed, while very much a daughter of this community, she takes full advantage of modern opportunities (use of social networks to communicate with people of her generation) agrees strongly with the fact that, for younger generations "calling into question the tradition, including the belief in the sacred, could be hazardous for the next generation." She insists that not aspects of modernity are to be taken on board.

These very clear positions of the women on the sacred show how they ensure the perpetuity of the modes of thinking and acting in society in general. It should be remembered that the initiation of young people to the sacred takes place from an early age and is ensured by the women, as we have also seen elsewhere: in Kayar, Yoff and Saint Louis.

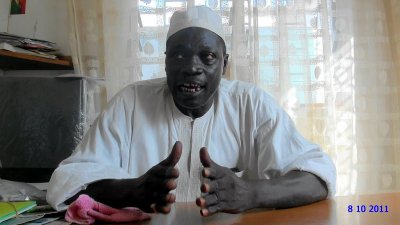

Place of the griot in society: Ousmane Diouf shows us one of their still unknown roles

Mouthpiece of the spirits to the community and the envoy to the Holy Priestess in Yoff

The griot is a key element of society, he plays important roles, which are still little known to the non-initiated.

The griot is a key element of society, he plays important roles, which are still little known to the non-initiated.

Indeed, it is recognised that the griots have always been poets, philosophers, mediators in disputes and advisors of those in power, a role reaching back into the ancient kingdoms.

But our mission, which focused on the role of the "sacred" in traditional fishing communities, was an excellent opportunity to discover another, extremely delicate, role of the griot.

But our mission, which focused on the role of the "sacred" in traditional fishing communities, was an excellent opportunity to discover another, extremely delicate, role of the griot.

This reminds us of other contexts, and by analogy, the complex function of some people, even in modern, contemporary administration.

This is, at least in the West African context, the Prefect: we sometimes do not know if he represents the State vis-à-vis the population or vice versa.

The Ndoep session begins with an incantation happening before the first day of the actual practice of this dance therapy.

The Ndoep session begins with an incantation happening before the first day of the actual practice of this dance therapy.

The first day is the key to the entire duration of this ancient practice to the extent that it is not only to seek the authoriation from the Spirits to make the Ndoep.

It is also to invite the spirits to be present among the population, in order to free patients from the obstacles preventing them to recover their initial health status.

The acceptance of the Spirits, who have the key remedies and therefore determine the success of the Ndoep, depends on the ability of the Griot.

The acceptance of the Spirits, who have the key remedies and therefore determine the success of the Ndoep, depends on the ability of the Griot.

The Griot is specialised in sacred music (transmitted according to heredity) and in incantations, to communicate the right message and enter into perfect communion with these Spirits.

The Griot is the link, which alone can decodes the message transmitted by the priestess in order to pass it on to the Spirits.

The Griot is the link, which alone can decodes the message transmitted by the priestess in order to pass it on to the Spirits.

But also, through the sacred music, he is the only one, who can ensure communication between the Spirits and the community.

Indeed, the incantations of the griot, and each rhythm played by the griot for the preparation and during the Ndoep, correspond to a specific Spirit.

It should be important to remember that the Lebu community is connected to many Spirits, some of which are located, according to tradition, in other coastal communities far from Yoff, such as Rufisque.

It should be important to remember that the Lebu community is connected to many Spirits, some of which are located, according to tradition, in other coastal communities far from Yoff, such as Rufisque.

But we are always referring to Lebu communities still traditionally dependent on fishing.