The mega event at FAO HQ in Rome from 18 to 21 November about fisheries sustainability attracted some 750 registered participants. Structured in fine detail, the eight sessions with up to six keynotes and an equal number of panels of five experts each per day placed a heavy emphasis on statements. That relegated discussions mostly into the few breaks and social hours. A large set of speakers, geographically, institutionally and thematically diverse and with good gender balance, summarised their current understanding of the status and expected futures of fisheries around the globe.

The mega event at FAO HQ in Rome from 18 to 21 November about fisheries sustainability attracted some 750 registered participants. Structured in fine detail, the eight sessions with up to six keynotes and an equal number of panels of five experts each per day placed a heavy emphasis on statements. That relegated discussions mostly into the few breaks and social hours. A large set of speakers, geographically, institutionally and thematically diverse and with good gender balance, summarised their current understanding of the status and expected futures of fisheries around the globe.

Peter Thomson, Special Envoy for the Ocean of the UN Secretary General, made a passionate plea during the opening ceremony to act urgently together for decisive ocean protection and climate protection. He recalled the high levels of extinction threats documented in the recently published assessment of global biodiversity (IPBES) also reflected with a record number of marine species being classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. Corals are expected to degrade further within a scenario of 1.5°C warming, but survive, while 100% will go extinct in a 2°C temperature increase. The extension of current trends will lead to a 3 to 4°C temperature increase. He underlined that the Special IPCC Report of the effects of accelerating climate change on the ocean and the cryosphere (polar ice cover and glaciers) pointed to faster observed change than anticipated in earlier modelling.

He lamented that humanity was at the moment doing everything it could to bring the ocean system and the climate onto its kneeds. He especially addressed the new FAO Director General Qu Dongyu congratulating him for his recent appointment. At the same time, only about six months away from the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, he cautioned that the Blue Economy discourse should not be supported if it amounted to a linear increase in exploitation of the ocean. If that trend could be changed into restraint and sustainable ways of using the ocean system and its resources, there would be hope.

He lamented that humanity was at the moment doing everything it could to bring the ocean system and the climate onto its kneeds. He especially addressed the new FAO Director General Qu Dongyu congratulating him for his recent appointment. At the same time, only about six months away from the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, he cautioned that the Blue Economy discourse should not be supported if it amounted to a linear increase in exploitation of the ocean. If that trend could be changed into restraint and sustainable ways of using the ocean system and its resources, there would be hope.

Therefore, Peter Thomson appealed to participants and responsible governmental and non-governmental organisations and agencies to work hard to stop IUU fishing, restore stocks to levels that could produce maximun sustainable yield around the ocean by raising effective management from around 14% to 100%.

He insisted in the face of some US$ 20 billion wasted on subsidies plain language was needed to stop squandering economic and ecological resources. He appealed to consumers everywhere to ask for proof that the fish they were buying or eating in restaurants was legitimate. He challenged businesses to become climate fit and produce - and earn - more on a sustainable basis.

He closed his appeal with demanding a New Deal for Nature - that should be the outcome of the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon in June 2020 that could inspire the agenda setting conference for biodiversity in China later in October. There is no more time to lose to respond to the climate crisis.

The Minister Michael Pintard from the Bahamas illustrated the urgency for action as the September storm with more than 180 km/hour wind speed had not only left 300 people dead, but also wiped out the results of decades of work. He underlined some protection approaches e.g. for sharks already taken by the country which made better nature and tourism business than exploiting the species relentlessly as elsewhere. But he also made it clear that the country could not hope to be sustainable on their island group unless all others took action to protect the ocean and the climate.

The Minister Michael Pintard from the Bahamas illustrated the urgency for action as the September storm with more than 180 km/hour wind speed had not only left 300 people dead, but also wiped out the results of decades of work. He underlined some protection approaches e.g. for sharks already taken by the country which made better nature and tourism business than exploiting the species relentlessly as elsewhere. But he also made it clear that the country could not hope to be sustainable on their island group unless all others took action to protect the ocean and the climate.

Not everybody saw it this way. For some, global fisheries were doing rather fine and only had need for some technical improvements, others brandished capture fisheries as a model at the end of its useful life to be replaced by aquaculture, while yet others saw opportunities for small-scale fisheries as a pillar of future food production from the sea and freshwaters, provided some of the negative policies and practical obstacles could be overcome in line with SDG 14 of agenda 2030. All agreed that there was room for greater social and other innovation and that challenges lay ahead in the face of a growing human populations and need to sustain food production within planetary boundaries.

The questioning on how to bring research results more effectively into various planning, policy and decision making processes focused very much on improving data collection. The demand for better and more comprehensive data on resources and their exploitation through various economic activities along value chains was understandably strong. A little less emphasis was placed on making better use of data, particularly by strengthening analytical capacities in countries with relatively weak statistical services and fisheries related institutions, including enforcement capacilities.

Will more data lead to better outcomes in terms of healthy resources and equitable sharing of cost and benefits? One would hope so, especially publicly available data and interpretations can help scrutinise and support management processes and empower citizens to support more precautionary approaches and lower risk policies.

Will more data lead to better outcomes in terms of healthy resources and equitable sharing of cost and benefits? One would hope so, especially publicly available data and interpretations can help scrutinise and support management processes and empower citizens to support more precautionary approaches and lower risk policies.

Some fisheries e.g. in the North Atlantic and around the US with strong data management and enforcement have improved over recent years, an encouraging development. But a measure of caution is in order as better data do not equate automatically with better management and greater fairness in allocation and sharing of benefits.

We observe that decisions are taken all the time under conditions of uncertainty even with quite incomplete data. It was repeatedly affirmed that such situations should not justify management failure but rather encourage use of more precaution. Moreover, when there is strong public scrutiny that will often create incentives for responsible management and also generation of better data. Can we reconcile marine food production with greater biodiversity protection? In sesson 3, it was all about seemingly hard trade-offs and difficulties where to draw the line between apparently conflicting objectives.

On the other hand, we know even without a massive additional data drive that many resources, particularly in the Mediterranean, Africa, Asia and Latin America are in decline from overfishing and not in the condition to produce the mandated "maximum sustainable yield".

Recent research presented briefly by Sally Yozell in session 8 pinned down China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea and Spain as the five top countries flouting the rules and involved in IUU fishing that plays a big role in the very wasteful use of resources in these regions. Allowing resources to recover would benefit both production and biodiversity.

Recent research presented briefly by Sally Yozell in session 8 pinned down China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea and Spain as the five top countries flouting the rules and involved in IUU fishing that plays a big role in the very wasteful use of resources in these regions. Allowing resources to recover would benefit both production and biodiversity.

The session on innovative technologies, e.g. vessel monitoring from systematic use of AIS signals to track fishing vessels as developed by Global Fishing Watch showed some new opportunities for creating greater transparency. But none of these will be silver bullets, but need flanking and supporting measures to increase compliance and better resource protection.

What does seem to provoke some consideration other than business as usual are probably climate change, the big disrupter, and more transparency and demand for greater accountability against a wider set of criteria.

That invites us to look in less conventional directions for solutions, and opportunities do exist for sure. Demands for social and environmental justice pervaded many sessions, if not always explicitly: the elefant in the room are continued subsidies to the industrial fleets, particularly of Asian and European countries. While formally it is the responsibility of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to deliver on SDG14.6 to phase out harmful, capacity enhacing subsidies by 2020, it still not entirely clear whether the relevant committee will achieve consensus, at least for vessels identified in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities. But without establishing a more level playing field, all declarations in support of small-scale fisheries will develop little tangible results on the ground.

Session 4 on small-scale fisheries made it clear that a lot needed to change for the better in order to ensure their sustainable and prosperous futures and keep delivering their significant contributions to food production for direct human consumption, food security and broad-base distribution of benefits. Speakers of fisher movements rejected the idea of associating small-scale fisheries primarily with poverty and hunger. They underscored their demands to be taken seriously as social, economic and cultural actors in management and policy making processes. That should go hand in hand with provision of better social services as available or under development for urban populations. The demand for gender equity and equality echoed also through several sessions given that women are estimated to account for about half the work force.

Session 4 on small-scale fisheries made it clear that a lot needed to change for the better in order to ensure their sustainable and prosperous futures and keep delivering their significant contributions to food production for direct human consumption, food security and broad-base distribution of benefits. Speakers of fisher movements rejected the idea of associating small-scale fisheries primarily with poverty and hunger. They underscored their demands to be taken seriously as social, economic and cultural actors in management and policy making processes. That should go hand in hand with provision of better social services as available or under development for urban populations. The demand for gender equity and equality echoed also through several sessions given that women are estimated to account for about half the work force.

How can we protect aquatic biodiversity and thus the future of productive marine and freshwater ecosystems while meeting growing food demands? Perhaps posing the question this way is not the most helpful perspective. It is unclear whether the projected increase in fish food needs is based on valid and realistic assumptions of a huge per capita increase of consumption while de facto per capita consumption e.g. in Africa hovers around half the current global average as a result of weak purchasing power and other food preferences in many inland regions. The blanket global projections make little or no reference to reducing current waste nor food preferences and should therefore be watched with a bit of caution.

What does seem clear though is that it's not going to be one size fits all. Better resource protection and recovery is a global need, but its most effective articulation needs to fit local, national and international conditions that will be most successful if based on participatory approaches, cooperation, gender equity and fairness in how costs and benefits are to be shared. That is also a promising way to make good use of novel technologies, be it to manage business better at all scales, be it to support rule enforcement.

What does seem clear though is that it's not going to be one size fits all. Better resource protection and recovery is a global need, but its most effective articulation needs to fit local, national and international conditions that will be most successful if based on participatory approaches, cooperation, gender equity and fairness in how costs and benefits are to be shared. That is also a promising way to make good use of novel technologies, be it to manage business better at all scales, be it to support rule enforcement.

During the last but one session keynote speaker Lori Ridgeway from Canada reminded the audience that being steeped too deeply in traditions can become a burden in the face of high levels of change and uncertainty. So, focussing exclusively on sector specific initiatives and policies was probably not the best way to prepare for the future.

Instead she invited FAO, governments and other actors to face up to the challenge of multi-dimensional policy making to account for the greater complexity shaping the presence and even more so the future. Fisheries was not an independent sector, but had to contend with many other powerful demands on the ocean and its resources. What was critical is to pay attention to tipping points and regime shifts. Maintaining access to resources required collaboration and forms of more inclusive governance.

She spotted a huge challenge to policy making at different levels and suggested exploring scenarios. Equity and better understanding what success could mean in this changed context could be helped by proactive engagement instead of still widespread defensiveness and avoidance. She also opined that high level political agreements needed to be broken down to operational level and changed courses of more equitable action. This needed publicly available reliable data for guidance, e.g. in relation to how the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries was being implemented. She cautioned that failing to engage with actors beyond the sector would lead to a very detrimental loss of ability to strive as independent actors in the ocean arena for viable fisheries.

That should be food for thought at the FAO and the next Committee of Fisheries (COFI) meeting which is to deliberate on innovative ways to contribute to the implementation of Agenda 2030 with emphasis on sustainable fisheries and food. Fish is mostly a healthy part of the diet and thus merits greater attention to sustainable production, consumption and access. This is particularly true for populations in need of a suffient and more balanced diet. A healthy ocean and healthy ecosystems are key to cope with climate change and other huge challenges. Aquaculture could not be assumed as the "easy" alternative in the light of significant feed limitations and new challenges from a warming ocean. Want it or not, change was in the air and already happening at significant scales, thus needing new and better answers.

That should be food for thought at the FAO and the next Committee of Fisheries (COFI) meeting which is to deliberate on innovative ways to contribute to the implementation of Agenda 2030 with emphasis on sustainable fisheries and food. Fish is mostly a healthy part of the diet and thus merits greater attention to sustainable production, consumption and access. This is particularly true for populations in need of a suffient and more balanced diet. A healthy ocean and healthy ecosystems are key to cope with climate change and other huge challenges. Aquaculture could not be assumed as the "easy" alternative in the light of significant feed limitations and new challenges from a warming ocean. Want it or not, change was in the air and already happening at significant scales, thus needing new and better answers.

Mundus maris was represented by Cornelia E Nauen who engaged actively in the conference with constructive questioning of several panels. She networked particularly with representatives of other civil society organisations. The early experiences with participatory learning and empowerments during the pilot phase of the SSF Academy in Senegal triggered interest in groups from other countries. They also believe that cooperation is a good way to contribute to fisheries sustainability and supporte FAO's mandate in this respect.

More information about the conference, the speakers and the results can be found here. All sessions were streamed on the web, so as to enable many more people to follow than were physically in the room.

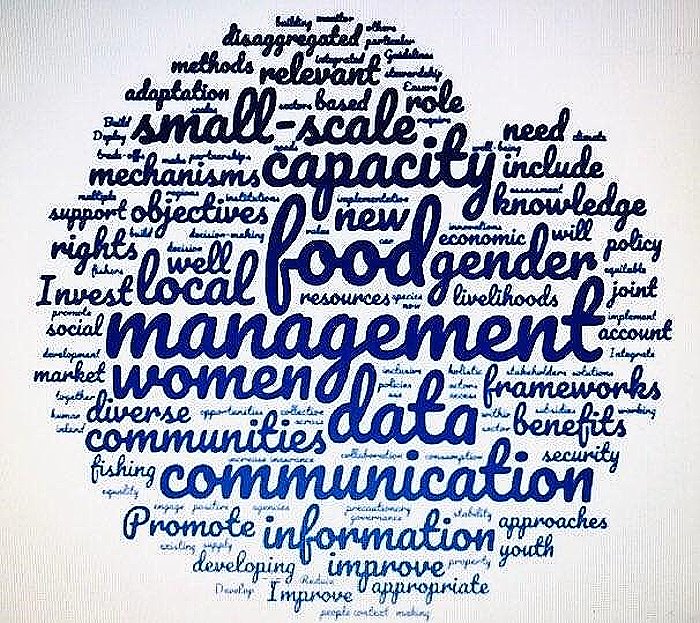

Draft key messages summarised at the end of the symposium from the participant polls during each session.