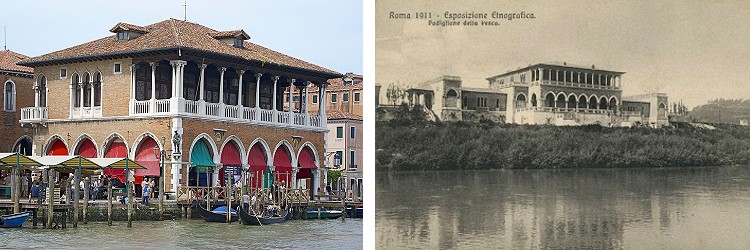

1911 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the unification of Italy, proclaimed in Turin on March 17, 1861, designating Rome as its capital, though it had not yet been annexed to Italian territory. The event was celebrated with a series of ethnographic exhibitions, the most notable of which was held in Rome in a space on the banks of the Tiber, then free from urban development. Wood and plaster pavilions were built, intended to be dismantled at the end of the celebrations. One pavilion might seem familiar to those who have studied the history of seafaring and fisheries in the Mediterranean. It faithfully reproduces the form and style of the Rialto Fish Market in Venice, built only four years earlier but in the early Gothic style.

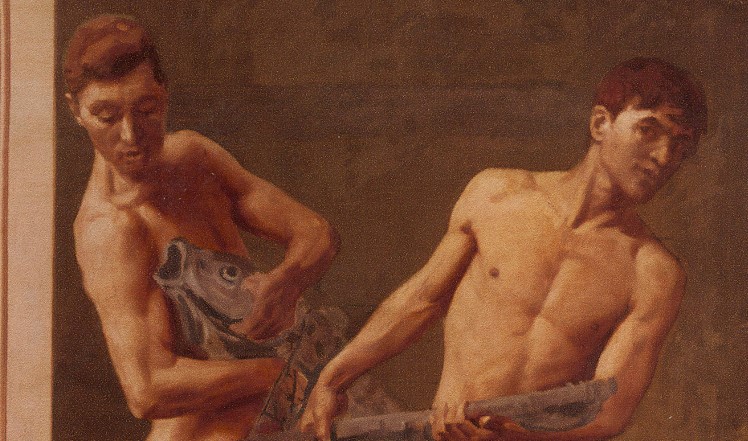

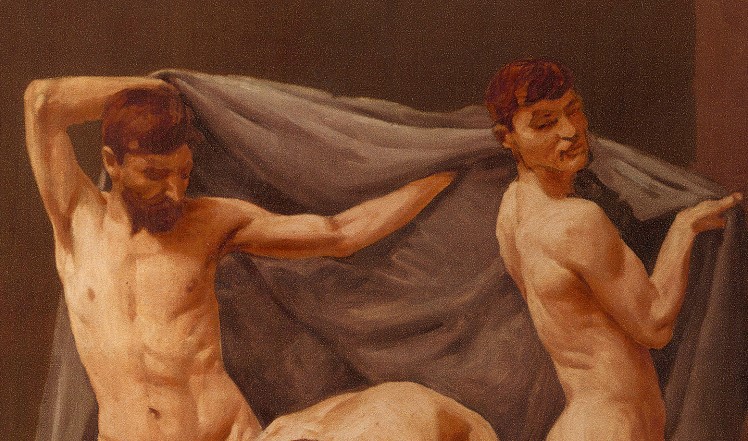

This is, in fact, the pavilion dedicated to fishing, rightly considered one of the most important and representative activities in Italy, a long peninsula stretching from north to southeast, embraced on all sides by the Mediterranean, what in ancient Rome was called Mare Nostrum. But the emphasis was not only on industrial and commercial activities, but also, and above all, on the human beings who played a key role in them. It was therefore decided that the pavilion’s loggia would be decorated with canvas paintings illustrating the fishing cycle, alternating with others depicting fishers with their catch and the gear they used.

The material collected was intended to be, and indeed was, the core of what became, thanks to the scholar Lamberto Loria, the Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions, currently incorporated into the larger complex of the Museum of Civilizations. It is located in Rome in buildings constructed for another major exhibition, the Universal Exhibition of Rome (EUR, as the neighborhood is still known today). It was planned for 1942 but was never held due to the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

On that occasion, large frescoes depicting some of the most important human activities were installed in the grand hall of what would later become the Museum. Here too, a significant space is dedicated to maritime life, with the vivid depiction of the tuna slaughter by the Calabrian artist Pietro Barillà (1887-1956).

The Museum also still displays numerous models of artisanal fishing boats, powered by sails or oars, along with nets and various gear, often from acquisitions made in 1911. They bear witness to fishing systems that were still human-scale and, above all, marine life-friendly, while today’s technology has allowed the use of systems that are too often predatory, with no thought for the future and no respect for the dignity of every living species.

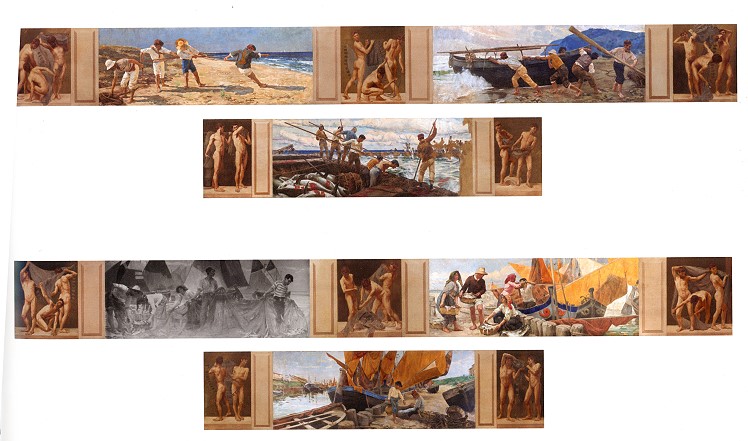

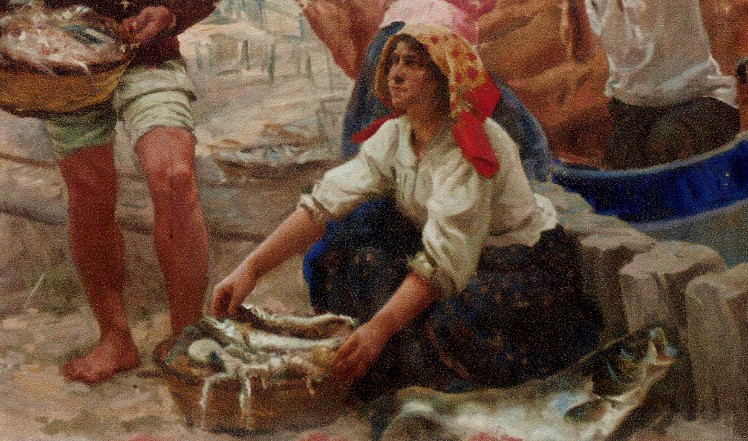

The Fishing Cycle (Ciclo della Pesca), created in 1911 by the Roman artist Umberto Coromaldi (1870-1948), remained lost for a long time. Finally rediscovered almost intact but in a degraded state at CREA (an institute for agricultural economics research and analysis), it was entrusted to the ICR, the Central Institute for Restoration, for a demanding restoration (the following photo is from the Institute’s Facebook page). It will soon be accessible to the public again, offering a glimpse into the important past of artisanal fishing in Italy, but perhaps also sparking thoughtful reflections on the future—in Italy, in Europe, and around the world.

Operazioni di restauro presso la sede dell’iCR

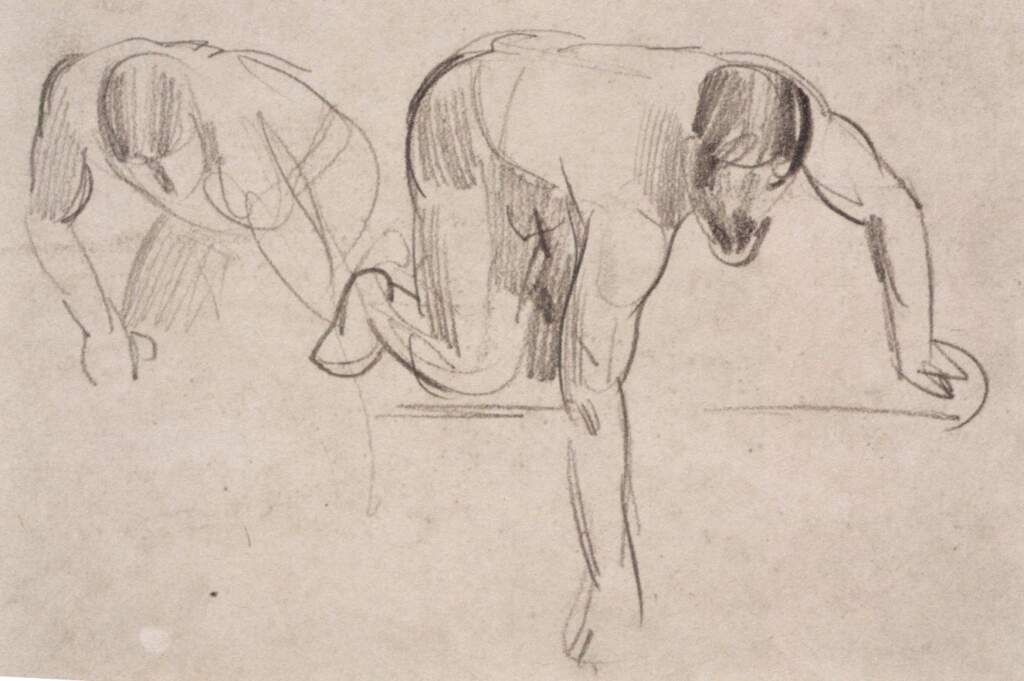

A recent publication, „The Fishing Cycle by Umberto Coromaldi at the 1911 Roman Exhibition“ (Il Ciclo della Pesca di Umberto Coromaldi nell’Esposizione romana del 1911 (ISBN 978-88-492-5244-6)), provides insight into the history of its discovery and restoration, and above all, offers a deeper understanding of the history and genesis of this crucial piece. In the following pages, we will examine in more detail some of the five panels (out of six) that were recovered, along with some of the – idealized yet significant – portraits of fishers.

The images accompanying this article are partly from the publication cited, partly from the public domain. Others were taken personally by the author at the Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions section of the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome, in August 2025. Also in this series – and this could not be left out due to its spectacular drama, but also its roots in centuries-old traditions – is the tuna slaughter. This recurring theme allows us to highlight the commitment of entire communities toward a common goal and their fundamental respect for the natural cycle of marine creatures, albeit often largely due to the absence at that time of the more effective, but more destructive modern technologies.

In the remainder of this article, we will briefly illustrate Umberto Coromaldi’s Fishing Cycle, attempting to highlight its artistic, documentary, and, above all, emotional value. This will allow us to relive, over 100 years later, the hard but profitable and sustainable daily work of the fishers of the past century.

Zwischen Tradition und Modernität

- The fishing cycle

- Die Geschichte des Störs

- Mundus maris participated in the 2024 World Fisheries Day organized by Canoe and Fishing Gear Association of Ghana (CaFGOAG).

- Challenges and Opportunities in the sustainability of Inland open water fisheries in India

- April V2V lecture – Vulnerability to Viability: Mind Matters

- Ein Blick auf Marsaxlokk, den traditionellen Fischereihafen auf Malta

- 2000 years ago: the ‚vivaria‘

- Interview mit Frau Khady Sarr im Kleinfischereihafen von Hann

- What the women in fisheries in Hann are saying

- Women in fisheries: Interview with Ms Ramatoulaye Barry, leader of a group of women fish mongers in Conakry

- Interview mit F. Soumah, Anführer von Kleinfischern

- A detour in the Boulbinet artisanal fishing port in Conakry, Guinea