Unter der Schirmherrschaft von MdEP Paulo do Nascimento Cabral, Mitglied des Fischereiausschusses und stellvertretender Vorsitzender der interfraktionellen Arbeitsgruppe SEArica, wurden in dieser Sitzung der EU-Ozeanwoche am Mittwoch, den 15. Oktober 2025, einige gute Beispiele für den Meeresschutz vorgestellt. Diese beruhen in der Regel auf der aktiven Beteiligung von handwerklichen Fischern oder wurden sogar von diesen initiiert.

Unter der Schirmherrschaft von MdEP Paulo do Nascimento Cabral, Mitglied des Fischereiausschusses und stellvertretender Vorsitzender der interfraktionellen Arbeitsgruppe SEArica, wurden in dieser Sitzung der EU-Ozeanwoche am Mittwoch, den 15. Oktober 2025, einige gute Beispiele für den Meeresschutz vorgestellt. Diese beruhen in der Regel auf der aktiven Beteiligung von handwerklichen Fischern oder wurden sogar von diesen initiiert.

Das Hauptziel des 300.000 Quadratkilometer großen Meeresschutzgebietes der Azoren – Blue Azores – ist es, die 140 Meeresberge mit ihrer Tiefseefauna zu schützen und generell die Biomasse wertvoller Meeresarten für den Naturschutz und eine lebensfähige lokale Fischerei wieder aufzubauen, aber auch z.B. für die weitere Entwicklung des Tauchtourismus und der Sportfischerei.

Die wissenschaftliche Dokumentation, z.B. der Gorgonien, Weichkorallen und tausendjährigen schwarzen Korallen, und die Kartierung verschiedener anderer Lebensräume wird durch entsprechende Aktivitäten in Schulen unterstützt.

Der für Fischerei und Meere zuständige Kommissar Costas Kadis, der an der Sitzung teilnahm, würdigte die MPA (Meeresschutzgebiete) als ein wichtiges Instrument zur Erhaltung der Funktionen und der Produktivität der Meeresökosysteme. Er brachte seine Überzeugung zum Ausdruck, dass das Ziel, 30 % der europäischen Gewässer zu schützen, nur mit guten Bewirtschaftungsplänen und einer starken Beteiligung der Bevölkerung erreicht werden kann.

Dr. Rui Martins, Regionaldirektor für maritime Angelegenheiten und Adriano Quintela, Spezialist für Meeresraumplanung, Programm Blue Azores, lieferten Details des Meeresschutzprogramms

Dr. Rui Martins, Regionaldirektor für maritime Angelegenheiten, und Adriano Quintela, Spezialist für Meeresraumplanung, Programm Blue Azores, gaben einen Einblick in das bisher Erreichte. Dennoch gibt es auch Herausforderungen, da einige Politiker geneigt sind, die Fischerei für Industrieschiffe in der Nähe von Meeresbergen nach 16 Jahren Sperrung wieder zuzulassen, aber die lokalen Fischer lehnen einen solchen Schritt ab.

Die Hälfte des MPA ist vollständig geschützt, die andere Hälfte ist stark geschützt.

Es ist sehr wichtig, einen möglichst hohen Standard des Schutzes zu gewährleisten, da halbherzige Maßnahmen nur die Gefahr bergen, dass sie potenzielle Nutznießer verärgern, ohne einen tatsächlichen umfassenden Nutzen zu bringen. Bislang sind 12,3 % der europäischen Gewässer als Meeresschutzgebiete ausgewiesen. Leider handelt es sich dabei meist um sog. Papierparks, in denen sogar die besonders zerstörerische Grundschleppnetzfischerei erlaubt ist. Das Ziel, bis 2030 30 % der Meeresgebiete zu schützen, scheint somit unerreichbar, selbst wenn nur 10 % vollständig geschützt werden sollten. Die Blauen Azoren zeigen die Vorteile eines echten Schutzes, wecken aber auch Begehrlichkeiten nach einem schnellen Gewinn auf Kosten aller anderen.

Würden die strengen Umweltvorschriften der EU durchgesetzt, z. B. die Vogelschutz- und die Habitat-Richtlinie, die Meeresschutz-Rahmenrichtlinie und das Verbot der Überfischung in der Gemeinsamen Fischereipolitik (GFP), würden die jährlichen Fangmengen nicht Jahr für Jahr zurückgehen, trotz des erheblichen und kostspieligen technischen Aufwands in der industriellen Fischerei.

Die Blue Marine Foundation arbeitet mit den Fischern vor Ort zusammen, um sich für vorsorgliche Ansätze im Einklang mit den Rechtsvorschriften und eine bessere Durchsetzung durch die nationalen und regionalen Behörden einzusetzen. Die vorgestellten Beispiele stammten aus Italien und Griechenland. Dr. Giulia Bernardi, leitende Programmmanagerin der Stiftung, und Santo Ruggera, Mitglied der Vereinigung für verantwortungsbewusstes Fischen in Salina, Sizilien, Italien, berichteten, wie die Fischer traditionelle Verfahren mit geringeren Umweltfolgen wiederbelebten. So wurde unter anderem die Zahl der Reusen, Langleinen und anderer Fanggeräte reduziert und stattdessen dank der von der Stiftung bereitgestellten Eisboxen auf Qualität gesetzt. An dem Projekt sind Schulen, Restaurants und lokale Fischhändler sowie die gesamte Gemeinde beteiligt. Die lokale Regierung hat die Initiative im März 2024 anerkannt.

Michalis Croessmann vom Berufsfischereiverband Amorgos, Griechenland, und Angela Lazou Dean, Senior Projekt-Manager, Blue Marine Foundation

Auf der griechischen Insel Amorgos haben die Fischer des lokalen Berufsfischereiverbandes (Professional Fishing Association of Amorgos) selbst die Initiative ergriffen, um drei Laichgebiete zu schützen. Im Laufe der Jahre mussten sie feststellen, dass ihre Fänge zurückgingen und die Verschmutzung zunahm, ohne dass ihre Beschwerden bei der Regierung Gehör fanden. Im Jahr 2021 begannen sie unter der Leitung von Michalis Croessmann mit der Umsetzung von Maßnahmen, um ihre Zukunft zu sichern. Sie hörten auf, während der Hauptlaichzeit im Frühjahr zu fischen, und nutzten stattdessen 2021 ihre Boote, um Müll von unzugänglichen Stränden einzusammeln. Dank einer Crowdfunding-Aktion und der Unterstützung durch den Cyclades Preservation Fund (CPF) und Enaleia konnten sie diese Maßnahmen 2022 fortsetzen und 15 Tonnen Plastik und 3 Tonnen verlorenes Fanggerät dem Recycling zuführen.

Die griechische Regierung akzeptierte die Ergebnisse einer einjährigen Untersuchung durch ein Team der Landwirtschaftlichen Universität in Athen, die die Einschätzung der Fischer bestätigte. Die formelle Anerkennung der drei Fischereiverbotszonen geht Hand in Hand mit dem Ziel, in allen Meeresgewässern des Landes 10 % streng geschützte Gebiete zu schaffen. Fortschritte sind möglich, wenn Menschen, Institutionen und Politik aufeinander abgestimmt sind.

Henrique Folhas, Experte für Erhaltung und Wiederherstellung der Meeresumwelt der Nichtregierungsorganisation SCIAENA, nutzte die Gelegenheit, um einen neuen Leitfaden mit 7 Tipps für MPAs (Merresschutzgebiete) vorzustellen (Guide with 7 tips for MPAs). André Dias, der aus einer Fischerfamilie stammt, erläuterte, dass in seiner Gemeinde in Albufeira an der Algarve, Portugal, die alten Fischer ihre uralte Kultur bewahren wollten. Dies geschehe durch den Schutz der Hartgestein- und Korallengebiete und der Produktivität der Ökosysteme, die diese Lebensräume erhalten. 14 von 17 Fischergemeinden unterstützten die Einrichtung und Durchsetzung einer Meeresschutzzone. Er kam zu dem Schluss, dass die Fischer in ihren Ruderbooten vor 100 Jahren etwa 100.000 Tonnen Sardinen fingen, während die leistungsstarken Industrieboote von heute nicht mehr als 30.000 Tonnen fangen können. Das sollte jeden zum Nachdenken anregen, wenn teurere, hochentwickelte Technologie als Lösung vorgeschlagen wird. Nicht nur zum Nachdenken, sondern auch zum Handeln in der Algarve und anderswo: weniger fischen, um mehr zu bekommen.

Nach den Präsentationen dieser Fallstudien und Initiativen erteilte der Moderator, Dr. Jean-Luc Solandt, Senior Project Manager, Blue Marine Foundation, den Teilnehmern das Wort. Cornelia E. Nauen von Mundus maris asbl erhielt die einzige Gelegenheit, sich zu äußern. In ihrem Beitrag machte sie drei Punkte deutlich:

- Was uns heute als überwiegend handwerkliche Fischerei erscheint, hat über lange Zeiträume Nahrung aus dem Meer für eine wachsende Bevölkerung geliefert. Die Technologien wurden im Laufe der Zeit immer ausgefeilter, aber zum größten Teil wurde dem Meer entnommen, was in einem Jahr nachwachsen konnte. Auf diese Weise konnte die europäische Fischerei im heutigen Neufundland 500 Jahre lang von den reichen Kabeljaubeständen zehren und zwischen 100 000 und 400 000 Tonnen Atlantischen Kabeljau (Gadus morhua) pro Jahr entnehmen. Mit dem Beginn der industriellen Großfischerei in den frühen 1960er Jahren stiegen die Fangmengen auf einen Höchststand von 1,4 Millionen Tonnen, was zum ersten Zusammenbruch führte. Nach einer kurzen Atempause kam es Anfang der 1990er Jahre zum zweiten Zusammenbruch, von dem sich die Bestände seitdem nicht mehr erholt haben. Die industrielle Fischerei brach der Bonanza das Genick.

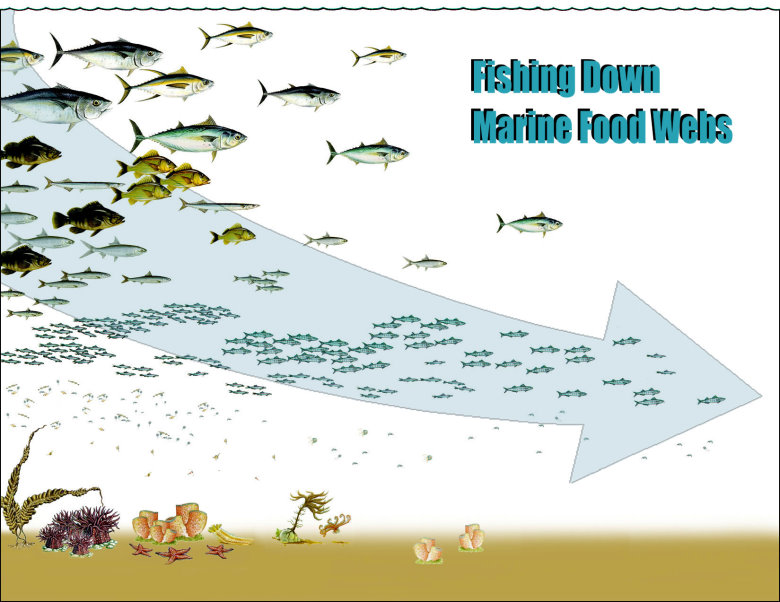

- Sich verändernde Rahmenbedingungen (shifting baseline) sind für viele Menschen, einschließlich der industriellen Fischer, ein großes Hindernis, die entscheidende Bedeutung von Meeresschutzgebieten für die Wiederherstellung der Gesundheit der Meere und der Produktivität der Ökosysteme zu erkennen. Sich ändernde Rahmenbedingungen bedeuten, dass sich jede neue Generation an dem orientiert, was sie zu Beginn ihrer beruflichen Laufbahn vorgefunden oder wahrgenommen hat. Die Faszination von Innovation und technologiefixierten Erklärungen überschattet die richtige Interpretation der aufeinanderfolgenden Zusammenbrüche von Fischgründen nach Perioden übermäßiger Fänge, die die Regenerationsfähigkeit der Ressourcen übersteigen. Der Wettlauf begann in den 1970er Jahren und führte dazu, dass immer weiter südlich oder nördlich gefischt wurde, sogar in Gebieten, die früher vom Polareis bedeckt waren, und in immer tiefere Gewässer, wo das Leben langsam ist und nur wenige Jahre industrieller Übergriffe ausreichen, um langlebige und sich langsam fortpflanzende Arten auszulöschen. Aber inzwischen gibt es für die Industrieflotten nichts Neues mehr, das sie noch zerstören könnten.

Quelle: Pauly D, Christensen V, Dalsgaard J, Froese R and Torres F (1998) „Fishing down marine food webs“ Science, 279: 860-863.

- Im Rahmen des Ozeanpakts und der Planung für eine gesunde und widerstandsfähige Zukunft der europäischen Meeresgebiete und eine sozial, wirtschaftlich und ökologisch tragfähige Fischerei muss die strategische Bedeutung der handwerklichen Fischerei anerkannt werden. Innerhalb einer Generation muss die industrielle Überfischung abgebaut werden. Dank der Umlenkung der schädlichen Fischereisubventionen hin zu einer positiven Regeneration der Ressourcen und der Wiederbelebung der handwerklichen Fischerei mit stationären Fanggeräten, die CO2-neutral sind und geringe Auswirkungen haben. Wir werden immer einige Wissenslücken haben, aber wir wissen genug, um zu handeln.

In seinen abschließenden Bemerkungen sah Marco Falcone, stellvertretendes Mitglied des Fischereiausschusses, noch viel Raum für einen vertieften Dialog. Was ist Europa bereit zu geben, um seine Meere wieder in einen guten Zustand zu versetzen?

Text und Fotos Cornelia E. Nauen. Einen ausführlicheren Bericht über zwei Meeresschutzinitiativen von handwerklichen Fischern, darunter die auf Amorgos, finden Sie hier.