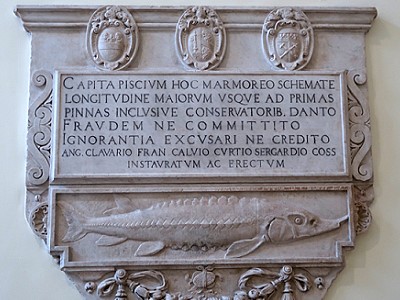

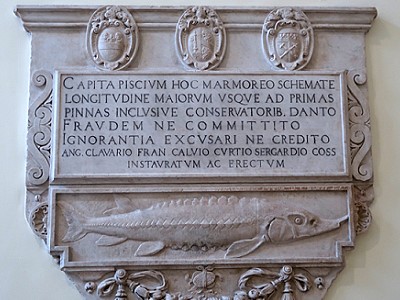

We are living in exceptional times: the covid-19 pandemic has affected Rome and many different parts of the world even more seriously. The memory of other essential aspects of life will do us some good. Like healthy and sustainable nutrition, like the memory of our past, recent or distant. On the staircase of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, which is located in the Campidoglio of Rome, on the right for those who enter from the magnificent square, there is a bas-relief of an uncertain era. It depicts a sturgeon, a fish present in the Tiber, the river that crosses the eternal city, until only some decades ago.

We are living in exceptional times: the covid-19 pandemic has affected Rome and many different parts of the world even more seriously. The memory of other essential aspects of life will do us some good. Like healthy and sustainable nutrition, like the memory of our past, recent or distant. On the staircase of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, which is located in the Campidoglio of Rome, on the right for those who enter from the magnificent square, there is a bas-relief of an uncertain era. It depicts a sturgeon, a fish present in the Tiber, the river that crosses the eternal city, until only some decades ago.

The inscription deserves to be examined:

The inscription deserves to be examined:

CAPITA PISCIUM HOC MARMOREO SCHEMATE

LONGITUDINE MAIORUM USQUE AD PRIMAS

PINNNAS INCLUSIVE CONSERVATORIB. DANTO

FRAUDEM NE COMMITTITO

IGNORANTIA EXCUSARI NE CREDITO

The heads of the longest fish of this marble plaque

up to the first fins included

They will be given to the conservatories

Do not commit fraud

The excuse of ignorance will not be believed

We thus learn about a tax established for the benefit of the Conservatories: They form a judiciary established in the thirteenth century and composed of three expert administrators who assisted the Senate of Rome in the government of the city and who resided precisely in the Palazzo dei Conservatori. The bas-relief shows the insignia of the three conservatories in charge in 1583.

But do not think that the heads were waste material, they were highly appreciated for making juicy soups.

The ancient sculptures donated by Pope Sixtus IV to the Roman people were deposited in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in 1471, making it the first museum in the world, today the Capitoline Museums.

The ancient sculptures donated by Pope Sixtus IV to the Roman people were deposited in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in 1471, making it the first museum in the world, today the Capitoline Museums.

They were, however, only opened to the public in the 18th century. It is customary to mention them in the plural as they also extend to the Palazzo Nuovo, built later on the other side in the square, and to part of the Palazzo Senatorio which is located at the bottom.

Recently part of the collection has been placed in a fourth museum area, the Montemartini Museum which is located along via Ostiense, the oldest street that led to Rome (it is thought to be almost 3000 years old) inside the former homonymous power plant.

The ancient statue of the god Tiber leaning against the Palazzo Senatorio paid tribute to the life force of the river, from which the mythical new founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were transported to safety. The two are shown here together with the she-wolf who fed them, who became and still is the symbol of Rome. A tangible trace of the cult of the waters is the name Tiberius, one of the most frequent in Rome, which belonged to the second Roman emperor.

In each of these museums, but also in others, such as the National Roman Museum, also in Rome, or the Archaeological Museum of Naples, it is not uncommon to find representations of fish.

In each of these museums, but also in others, such as the National Roman Museum, also in Rome, or the Archaeological Museum of Naples, it is not uncommon to find representations of fish.

Fish are of represented in mosaic, which adorned the homes of the wealthiest Roman citizens. They usually date back to the imperial age. So they are between 1500 and 2000 years old.

But what relations did the Romans have to fish and its consumption?

Fish was widely consumed and held in high esteem. The finest specimens could reach hyperbolic prices, as evidenced by the colourful anecdotes of numerous writers, but also by the first encyclopedia handed down to us: the Historia Naturalis of Gaius Plinius Secundus, admiral of the Roman fleet of the Mediterranean, and great scholar. He died in 79 AD, victim of the eruption of Vesuvius, which destroyed the cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabia. He had gone to study the eruption closely after having ordered that the fleet intervene to help the population.

We know from him that the fish bred by the leader Lucullus at Lake Lucrino, not far from Naples, were sold after his death for 40,000 sestertii, and that the modest villa of Gaio Irrio, which had supplied Giulio Cesare with 6000 moray eels for celebration rituals, was sold for 4 million due to the value of its nurseries.

We know from him that the fish bred by the leader Lucullus at Lake Lucrino, not far from Naples, were sold after his death for 40,000 sestertii, and that the modest villa of Gaio Irrio, which had supplied Giulio Cesare with 6000 moray eels for celebration rituals, was sold for 4 million due to the value of its nurseries.

And also the speaker Ortensio, an opponent, but sometimes Cicero's colleague, was so fond of one of his Mediterranean morays (Muraena helena) that as he mourned its death, the princess Antonia Maggiore adorned his favorite moray with earrings.

Pliny also provides less anecdotal information: for example that among the most renowned fish were red mullet (Mullus barbatus), which could not be bred and rarely exceeded the weight of two pounds (about 700 gr).

He noted that the parrot fish were introduced to Italy by Claudius Optatus, the prefect of the Tiberian fleet, who imported them from the Lecto promontory (in present-day Turkey) into the Tyrrhenian Sea. For five years, Claudius Optatus took care that all those caught were put back into the sea so that they could spread.

![]() Pliny also reported that during the reign of Caligula the former consul Asinius Celeris purchased only one specimen of red mullet for 8000 sestertii.

Pliny also reported that during the reign of Caligula the former consul Asinius Celeris purchased only one specimen of red mullet for 8000 sestertii.

We find traces of all this also in poetry: in fact, Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis (about 60-120 AD) comes to our aid in his fifth satire, in which he rages on the expensive culinary habits of nobles and Romans in general, but also denounces environmental degradation:

Mullus erit domini, quem misit Corsica vel quem

Tauromenitanae rupes, quando omne peractum est

et iam defecit nostrum mare, dum gula saevit,

retibus absiduis penitus scrutante macello

proxima, nec patimur Tyrrhenum crescere piscem.

Instruit ergo focum provincia.

Translation:

Then there will be a red mullet for the owner which

came from Corsica or from the rocks of Taormina;

the fishing nets constantly rummage on our seabed

and let no fish grow in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The Province therefore provides our cuisine.

The Mediterranean morays were highly appreciated, to the point that even today we wonder if they took the name from the first Roman who managed to raise them, Sergius Licinius Murena (1st century BC).

The Mediterranean morays were highly appreciated, to the point that even today we wonder if they took the name from the first Roman who managed to raise them, Sergius Licinius Murena (1st century BC).

Or was it not rather he who was nicknamed Murena due to his fish raising activity? The same can be assumed of Caius Sergius Orata, who obviously introduced the breeding of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata).

Virroni muraena datur, quae maxima venit

gurgite de Siculo; nam dum se continet Auster,

dum sedet et siccat madidas in carcere pinnas,

contemnunt mediam temeraria lina Charybdim.

Translation:

For Virrone here is a giant Mediterranean moray

from the whirlpools of Sicily:

when the Austro calms down, while resting in a cave and drying its soaked wings,

temerary sails defy the center of Chariddi.

Here we also learn, at least according to Iuvenalis, that the morays found shelter and were fished when the south wind ceased, albeit challenging the insidious waters of the straits that separate Italy from Sicily, guarded according to legends by the two sea monsters, Scylla and Charybdis.

But if the morays were reserved for the high-ranking class, the Tiber fish, which were not always sturgeons, were reserved for the crowd of their followers:

But if the morays were reserved for the high-ranking class, the Tiber fish, which were not always sturgeons, were reserved for the crowd of their followers:

vos anguilla manet longae cognata colubrae

aut glacie aspersus maculis Tiberinus et ipse

vernula riparum, pinguis torrente cloaca

et solitus mediae cryptam penetrare Suburae.

Translation:

And what is there for you?

An eel, a cousin of a long snake, awaits you

or a spotty fish, caught in the Tiber,

one of those who frequent our shores,

fattened by the drains of the cloaca, one

used to going back up the sewers to the Suburra.

The notion, or at least the popular belief, that the drains of the sewers fattened the fish is also confirmed by Livius. He reports that the best pikes (Esox lucius) of the Tiber were found in the area between the two bridges, that is where the largest sewer of Rome was discharged, the Cloaca Maxima, a grandiose artifact that discharged all waters, but not only sewers, into the river. It was built in the fifth century BC to drain the marshes in the area.

Some notions that have survived for a long time have been collected by the writer Giggi Zanazzo (1860-1911). He filled four volumes with Popular Roman Traditions. In the appendix written in Roman dialect he reports in a description on p. 89:

Some notions that have survived for a long time have been collected by the writer Giggi Zanazzo (1860-1911). He filled four volumes with Popular Roman Traditions. In the appendix written in Roman dialect he reports in a description on p. 89:

I romani antichi lodavano il pesce lupo, come squisito, specie quello che si pescava tra i due ponti Sublicio e Palatino, per l'imbocco della Cloaca Massima. Lo afferma Caio Tizio, riportato nel 16. del terzo dei Saturnali di Macrobio.

Translation:

The ancient Romans praised the wolf fish as exquisite, especially the one caught between the two Sublicio and Palatine bridges becaise pf the discharge of the Cloaca Maxima. This was stated by Caius Tizius, reported in sixteenth of the third book of Macrobio's Saturnalia.

In the short chapter dedicated to river people, he also documents the various fishing methods with line or net, including the "gurnard" or "girarello", two rotating nets moved by the current, and some of the most sought-after preys:

barbels (Barbus barbus),

barbels (Barbus barbus), - sharks,

- Blackspot seabreams (Pagellus bogavareo),

- eels (Anguilla anguilla),

- Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus), etc.

Still in the 1950s, the banks of the Tiber downstream of the Cloaca Maxima, were thick with fishermen, both anglers and fishers with lift nets. At the end of the century, some fishermen specially loved the sewer outlet. It was not unusual to see them come up from the banks with carp longer than 50 cm.

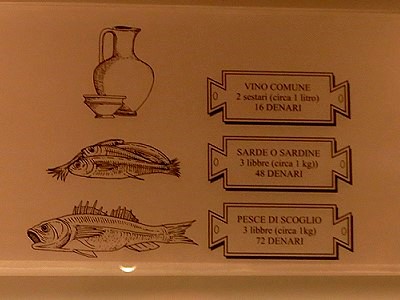

Having said that, the matter of the fish fauna of the Tiber was treated by Paolo Giovio (1483-1552) in his work De romanis piscibus libellum, 1531, we still want to satisfy a curiosity: exceptions and expensive extravagances aside, what was the price of fish in current use in ancient Rome? Emperor Diocletianus (244 - 313 a.D.) comes to our rescue with his edict De pretiis rerum venalium (The prices of commodities) of 301:

.

.

| Wheat | 10 kg | 81 denarii |

| Chicken | 2 | 60 denarii |

| Wine | 1 l. | 16 denarii |

| Round sardinella or pilchard | 1 kg | 48 denarii |

| Rockfish | 1 kg | 72 denarii |

The denarius argenteus was introduced precisely by Diocletianus in his monetary reform, of which the edict was an integrated part. it had a weight equal to 1/96 of a pound, about 3.4 grams. Here n the table it was, however, the denarius communis, whose value was 1/100 of the silver money.

These measures aimed to contrast inflation at the time: It should be remembered that, about 270 years earlier, 30 denarii customarily would buy much more ...

Paolo Bottoni, 2020